Standard International English? Part 1

Standard International English? Part 1

by Charles Lowe

Part 1 - World Englishes

Executive Summary

This article is in three parts, and it makes the case for a Standard International English. In Part 1, an alternative to Kachru’s concentric-circles model is suggested for how we understand the idea of World Englishes. Part 2 considers the merits and demerits of English as a Lingua Franca, or ELF. And in Part 3, I argue why a standard is necessary, and posit a model, both of the thing itself and of the process by which we might arrive at it.

Part 1

Introduction

The aim of learning English, for most students, is to become effective in using International English, i.e. to be able to use English to operate successfully in the world. In my view, their aim is not to try to speak like a native speaker, and not, in the words of Pawley and Syder (1983), to achieve ‘native-like fluency’. Indeed, ‘native-speakerism’, first criticised by Holliday (2006), has become a slightly pernicious force in ELT, with academic treatises (Paterson 2020) and textbooks (Dellar et al 2018) now firmly guided by it.

In this part of the article, I will introduce the idea of World Englishes that underpin any discussion of English as a Lingua Franca (ELF). The most common starting point in discussions of ELF is Kachru’s ‘concentric-circles’ model, but I believe that it needs updating, and even correcting, so that it has more relevance to ELT. In the second part, I want to reframe ELF itself, so that in the wider context, it has a place, but may not be a viable objective for language teachers, because it is based on pragmatic language use. And finally, in Part Three, I want to propose a model of ‘standardised international English’, which can be taught by native-speakers and non-native speakers alike.

Kachru’s model replaced

Sidney Greenbaum (1985) suggested that, rather than talking about a monolithic ‘standard English’, we should talk about World Englishes (i.e. not only British English, US English, and Canadian English, but also Indian English, Singaporean English, Ghanaian English, etc). But ever since that moment, a sort of collective middle-class guilt seems to have descended over teachers from the former colonial power, the UK. This has taken several forms. Firstly, many ELT professionals felt that, no matter where English was spoken as a first language, each of those Englishes was in fact a form of Native Speaker English, and should therefore have equal status to every other English spoken as a first language. Secondly, it was felt that the native-speaker English specifically of the UK, because it was the English of the former colonial power, was culturally tainted because it carried a linguistically imperialist connotation and therefore a falsely dominating position (e.g. Phillipson, 1992). Thirdly, the question was raised: who owns English? The puzzle created by this declaration of the ‘rights’ of native speakers, from wherever they hailed, was that some of those Englishes were often not intelligible to many non-native speakers of English, such as Germans or Brazilians who had acquired only an ‘intermediate’ level of L2 English.

Kachru (1986) sought to unravel this conundrum by suggesting a model which incorporated three types of English-language speakers. Kachru’s model stated that there are three concentric circles depicting different types of English which effectively ‘spread out’ from the centre – inner circle native speakers of English from the US, the UK, Australia, Canada, South Africa, Ireland, and New Zealand, outer circle speakers from India, Singapore, Ghana, Nigeria, etc, (who either speak their own version of English as a Language or speak English as their Second Language), and expanding circle non-native speakers (i.e. all those people who are learning English as a foreign language). Despite the implicit value judgement here, namely that some of the ‘Outer Circle’ Englishes are a lesser form of Native Speaker English (NSE), it does appear more realistic, on the face of it, to hold these outer circle Englishes in a separate category.

The responses to Kachru’s model were many and various, but one of the biggest in terms of the development of English as a Lingua Franca came from Jennifer Jenkins.

Jenkins’ seminal and thought-provoking work (2003) contains a historical review of the growth of theoretical ideas about what she called English as a Lingua Franca (ELF). She critically outlined the development of models by Strevens, Kachru, McArthur and, in particular, Modiano. Modiano broke completely with Kachru’s historical and geographical concerns and suggested a ‘centripetal’ model, with ‘mutual comprehensibility’ among speakers of English, both native and non-native, as the core principle. He enhanced this model a short while later (Modiano, 1999) to include both mutual comprehensibility of phonology and core features of grammar and syntax and lexis, and gave his core language the name ‘English as an International Language’ (EIL). Surprisingly, Jenkins makes a criticism of Modiano at this point in her work, which is both incorrect and redolent of the ideological prejudice that characterises much of her subsequent writing. She accuses him of implying that all native speakers are ‘competent’ users of English, which he clearly does not, identifying instead that native-speaker features peculiar to their own speech communities (whether in Indian localities or in working-class Glasgow – my parenthesis) may often render those communities incomprehensible within the ‘core’. This is an error, and one which I think is compounded by the fact that some of her later writings seem to be founded on this wilful misinterpretation.

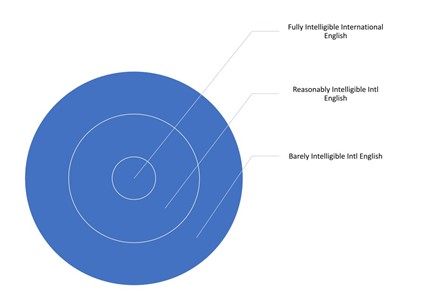

Modiano unpacked an important issue. And in a similar vein, a rational model of the variety of Englishes spoken has been put forward by Emmerson (2005). To get away from the value-laden idea of native and non-native speakers of English, Rampton (1990) first expounded the notion of ‘expert users’ and ‘non-expert users’. Emmerson (ibid), pursuing a different but related theme, has suggested, like Modiano, that ‘mutual intelligibility’ is the key to any model of speaker differences, and he is clearer than Modiano about how this mutual intelligibility works. As is shown in Figure 1, his Inner Circle, of Fully Intelligible International English, now represents (i) non-native speakers with a very good level of English, and (ii) native speakers who can speak quite slowly, with standard pronunciation and grammar, and who can grade (i.e. simplify) their language’ (Emmerson, ibid). His Middle Circle, of Reasonably Intelligible International English, represents (i) non-native speakers with a fair level of English, and (ii) native speakers who speak without a strong accent and who have some idea about minimising their idiomaticity. His Outer Circle, of Barely (my word – Emmerson says ‘partially’) Intelligible International English, will either represent non-native speakers with a low level of English, or native speakers who speak with high levels of idiomaticity, or native speakers who speak with high levels of local dialectal variation, often called ‘basilect’ (e.g. Cornish dialect in the UK, Singlish in Singapore), or native speakers who speak with a strong accent (whether Glaswegian, Texan, Indian, or Nigerian), or native speakers who speak too fast. We will call these groups “naïve native speakers”.

Figure 1

Kachru’s model, as has been said, is driven by historical and geographical perspectives. From this point of view alone, it has surely nothing to offer the professional discussion of English Language Teaching in the present day. Yet it is used as the jumping-off-point, the sine qua non, for almost all discussion of both International English and English as a Lingua Franca. The implications of Modiano’s and Emmerson’s models, both much more pedagogically relevant than Kachru’s, are (i) that many Native Speakers who would automatically be relegated to Kachru’s (second) Outer Circle (e.g. Singapore), would now, if they speak ‘intelligibly’ under Emmerson’s criteria, be included in Emmerson’s Inner Circle, (ii) that native and non-native speakers are not separated by type, and that mutual intelligibility can include both groups if they meet the criteria, (iii) a large number of native speakers will be included in the Barely Intelligible ‘outer circle’ (a fact also implied by Modiano), because, as naïve language users, they are simply incapable of knowing what kind of problems their international interlocutors have when they speak English, and are therefore incapable of knowing how to make themselves understood in International English contexts. Indeed, many of our business English students at IH complain that the only members of their international management teams that cannot be understood are the British managers, who speak without self-awareness, at speed, with high idiomaticity, and with slovenly pronunciation, and (iv) many non-native speakers speaking only to other non-native speakers – this is Jenkins’ English as a Lingua Franca (ELF) – will be in the Middle Circle, not, as in Kachru, the Expanding Circle.

Emmerson does not explore in detail the nature of mutual intelligibility – how it is arrived at, how it is measured, or indeed how it might be taught. And unlike Modiano’s model, it does not refer to a core of English which might be comprehensible in terms of phonology and grammatico-syntactico-lexical features. But it is certain that it better categorises the nature of English-English interactions around the world than Kachru’s model.

There is no doubt that, at the centre of the entire debate about English as an International Language is the issue of ideology. And on this point, it may be that the ultimate individual response from each participant in the debate is: you pays your money and you takes your choice. On the one hand, there are those who follow Robert Phillipson’s view, as expressed in his book Linguistic Imperialism (1992), that the growth of any international lingua franca is a bad thing because it kills off the ‘biodiversity’ inherent in organic language use and cultural identity. On the other hand, as Jenkins quotes (2003:34), Telma Gimenez thinks English provides the basis for ‘planetary citizenship’.

But in this article, I seek to argue that the choice offered so far may be irrelevant to the actual solution that I offer. Just as in France and the US, where the core national cultures simply act as an underlay to cultural identity and cultural diversity, I want to argue that a Standard International English (SIE), properly described, fully functional, globally comprehensible, yet with in-built organic potential for growth and local ownership, is possible. I want to argue that such a SIE can and should act as an underlay for global communication, while avoiding interference with cultural identity or other languages.

Conclusion

I have suggested that Kachru’s concentric-circles model is inappropriate to the discussion of pedagogy. As such, it being the basis on which claims are made for English as a Lingua Franca (ELF), it seems to me that ELF is already tarnished before it makes its pitch. However, as I say in the next two parts, ELF can be seen as an essential component of the wider picture.

Bibliography

Dellar H, Walkley A (2018) Outcomes, Boston, Cengage

Emmerson P (2002) Business Grammar Builder, Oxford, Macmillan

Emmerson P (2005) ‘L3, the new Inner Circle, and International English’ in The IH Journal of Education and Development, Vol 19, Autumn 2005

Emmerson P (2007) Business English Handbook: Advanced, Oxford, Macmillan

Greenbaum S (1985) The English Language Today: English in the International Context, London, Prentice Hall

Holliday A, (2006) ‘Native-Speakerism’ in ELTJ 60/4 October 2006

Jenkins J (2003) World Englishes: A Resource Book for Students, London, Routledge

Kachru B (1986) The Alchemy of English: The Spread of Alternative Englishes, Oxford, Pergamon Press, reprinted 1990, Urbana: University of Illinois Press

Modiano M (1999) ‘Standard Englishes and educational practices for the world’s lingua franca’, in English Today, 16/2

Paterson K, (2020) A Handbook of Spoken Grammar, DELTA Publishing

Pawley A K, Syder F H (1983) ‘Two puzzles for Linguistic Theory: Native-like selection and Native-like Fluency’ in Richards JC and Schmidt RW Language and Communication, London, Longman

Rampton B (1990) ‘Displacing the ‘native speaker’: expertise, affiliation, and inheritance’ in ELTJ 44/2 1990

Author Biography

Charles Tim Lowe has been involved in ELT since 1975. He has taught and trained in several countries, written extensively on ELT, and, after completing his MA, lectured at the Institute of Education London University. He established the original Distance DTEFLA, and managed two flagship language schools. Now, having taught EAP and CLIL for 6 years at Sophia University Tokyo, he has returned to teach English at IH London, where he once again teaches both General and Business English.

Charles Tim Lowe has been involved in ELT since 1975. He has taught and trained in several countries, written extensively on ELT, and, after completing his MA, lectured at the Institute of Education London University. He established the original Distance DTEFLA, and managed two flagship language schools. Now, having taught EAP and CLIL for 6 years at Sophia University Tokyo, he has returned to teach English at IH London, where he once again teaches both General and Business English.