5 Ideas to Make the Most out of Readers

5 Ideas to Make the Most out of Readers

by Pilar Capaul

As teachers of English, we have a multitude of responsibilities: from exam preparation to turning textbook explanations into engaging tasks, our time is often stretched thin. With so many competing demands, it can be challenging to find ways to incorporate extensive reading activities into our classes. However, we should be aware that this is an essential component of language learning and can help our students develop their language skills, increase their vocabulary, and improve their comprehension. "The more someone reads, the more they pick up items of vocabulary and grammar from the texts, often without realising it, and this widening language knowledge seems to increase their overall linguistic confidences [...]” (Scrivener, 2005).

What can we do in order to comply with all these tasks? In this article, I will present five simple ideas that can help us get the most out of our learners as readers, even with limited time. These are low-preparation yet effective ideas that have helped my students and I make the most out of our favourite stories, and hopefully they will help you and your students too.

Before reading

1. What type of reader am I?

Encouraging students to understand the type of readers they are is an important step in helping them become more successful and confident ones. By understanding their reading strengths and weaknesses, they can identify areas they need to work on and develop strategies to improve. Knowing their reading level and style can also help students choose books that are appropriate for their skill level and interests, which can increase their motivation to read.

Where should we get this material from? We can provide our students with a ready-made quiz from the Internet, we can come up with open or multiple-choice questions ourselves (making sure we include new lexical items or structures we´ve been working on during the year), or we can encourage them to come up with their own set of questions by working in groups. The key here is that there are lots of ways to adapt this activity to the needs and interests of our learners together within our physical and temporal constraints.

To give this self-discovery task a sense of closure, the students can interview each other and write a paragraph or text sharing their findings, they can use the information they´ve gathered and make a presentation on the reading habits of the group they work with, or they can even come up with a set of tips to motivate their classmates to develop themselves as readers.

Once we have the book

2. Judge a book by its cover

This is a very simple yet thought-provoking Canva-inspired activity to get students to start thinking about the contents of a new book, the characters they're about to “meet”, and how different structures and words - many of them new! - will take them through new settings and experiences.

(Source: Canva)

We can provide our students with a complete questionnaire to guide their thoughts in order to create detailed hypotheses on the contents of a new story, or we can just provide them with a piece of paper to write their thoughts on as a new cover, where typography and title play with their previous experiences and expectations. Whatever approach we decide to go with, we are going to need to keep our students' ideas somewhere safe - put those pieces of paper in a folder, stick them on a poster in the classroom, etc - and go back to them both as we read and once we’re done with the story. Ask students to compare and contrast their expectations of the contents and language used in the book with what they actually read. "A [book] in any language is studied more effectively if students are given a specific purpose, not merely told to read and make notes" (Nuttal, 1996). Having a single activity that keeps students engaged in their reading is bound to make the process a more meaningful one.

Bonus: As time goes by, you’ll notice students won’t just correct themselves in terms of content, but they’ll most probably also be able to correct their own use of language. This is why this activity also acts as proof of our students’ progress throughout the year.

As we read

3. Character analysis through GTKY Activities.

Character analysis, although a nice method by which to work on both comprehension and vocabulary, can also be a complex and time-consuming task within the bounds of a ninety-minute lesson, especially if students are also expected to engage in other activities. One way in which we can reduce that burden is by asking students to think about the characters in the story and pick the one they identify with the most to complete different GTKY activities they’re already familiar with, such as playing GTKY Bingo, coming up with a set of interview questions to use in a role-play, playing two truths and a lie, never have I ever, or finding three things in common.

If the story or book we’re working with is rather long, we can invite our students to keep a journal and write weekly entries covering different topics from that character's perspective.

4. Using graphic organisers:

(Source: Canva)

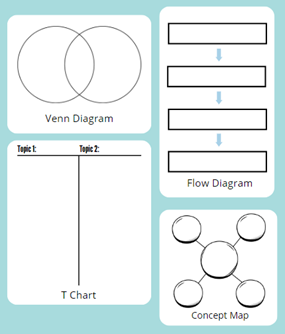

Another thing we can do to encourage our students’ creativity is to provide them with a set of random graphic organisers, and invite them to fill them by finding connections between the characters, settings, and events described in the story from the angle they find most interesting.

Although the instructions may seem a bit vague at first, we can make it more and more specific by asking students to make use of certain language points we believe they need some extra work on: let’s suppose five students in the group find it difficult to use narrative tenses, two others keep using the same vocabulary items over and over again even though we’ve worked on a variety of new words to expand their vocabulary, and the rest of the members of the class could use some practice on speaking.

We can ask the first three to use a flow chart and complete it with key events that guide the story, which they can then narrate and develop in a text, and we can give the other two a T-chart to be completed using new words that match different characters’ personality and physical traits and then use them to write a full description. Finally, we can invite the rest of the class to use a Venn Diagram to compare their lives with those of the protagonists of our book or story.

After reading

5. BookTube & Bookstagram:

This is the name of the trend in which passionate readers record themselves sharing their key takeaways from books they have read. Even if we are not going to ask our students to share this type of material on the Internet, we can select a couple of good examples to analyse together in class. We can brainstorm ideas on key elements to include when creating a BookTube-worthy video and invite students to work in groups and use them as guiding points to write a script. For example, we could ask students to include a brief summary of the book, their opinion on it, and any favourite quotes or scenes, etc. With new social media platforms, we now have more available options: students can use their ideas to create some Bookstagram-worthy content. Bookstagrammers create Instagram posts, reels, and stories to share their take on their readings, which gives us teachers a wider range of options to work with for both speaking and writing. Once the groups are ready, we can have each group present their Booktube scripts to the class as part of an oral presentation.

Final words

As teachers of English, we understand the challenges that come with balancing multiple demands on our time; as Jeremy Harmer very well stated it, “The need for surprise and variety within a fifty-minute lesson is also overwhelming” (2007). Still, there is always a (low-prep) way to incorporate extensive reading activities into our classes as an essential component of language learning. It is through our persistence as teachers in encouraging our students to read regularly together with some engaging tasks that our students achieve their language learning goals and become lifelong readers.

References

Education Resource Hub, (n.d.). Reading Reflection Worksheet [Template]. Canva. https://www.canva.com/templates/EAEqD9O7qWI-reading-reflection-worksheet/

Harmer, J. (2007). How to teach English-New edition. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

Scrivener, J., & Teaching, L. (2005). Macmillan Books for Teachers. Learning Teaching. A guidebook for English language teachers: Macmillan.

Nuttall, C. (1996). Teaching reading skills in a foreign language. Heinemann, 361 Hanover Street, Portsmouth, NH 03801-3912.

Author Biography

Pilar Capaul is a 23-year-old teacher and student teacher from Argentina. She teaches English at International House Buenos Aires and Spanish as a Foreign language at Porteñisima. She passed her CELTA at Grade A and her IHC in Teaching Spanish as Foreign Language with Distinction. She has delivered talks for International House and TESOL in the last couple of years. She's also the creator of @TeachersofEnglish_ on Instagram, a blog where she shares her daily teaching experience and useful ideas.

Pilar Capaul is a 23-year-old teacher and student teacher from Argentina. She teaches English at International House Buenos Aires and Spanish as a Foreign language at Porteñisima. She passed her CELTA at Grade A and her IHC in Teaching Spanish as Foreign Language with Distinction. She has delivered talks for International House and TESOL in the last couple of years. She's also the creator of @TeachersofEnglish_ on Instagram, a blog where she shares her daily teaching experience and useful ideas.