Creative writing at a critical age: Using poetry to stimulate creativity and embrace writing skills in teenage classes

By Keely Laufer

A class creative writing project using authentic materials can be created to challenge, train and develop general writing skills and teach a variety of sub-skills to higher level teenagers, such as creative and critical thinking and editing skills. Creativity involves imaginative, innovative and abstract thinking, and critical thinking involves logic and reasoning, questioning, analysis, assessment and evaluation. When carried out as a long-term class poetry project, these skills combined can help teenagers to express their opinions, attitudes, emotions and sense of self in L2 sooner.

Coursebooks for teenagers do not always provide much opportunity for integrating creative and critical thinking and writing skills into language learning to help students achieve higher levels of self-expression, not only needed for FCE and beyond, but to motivate teenagers by making language learning an enjoyable experience. As Michael Lewis asserts, ‘Syllabuses are directed towards language teaching, but ultimately it is not languages which are being taught, but people. People want and need to express emotion and attitude’ (see note 1). My aim was to help my BKC ‘English in Mind 4’ students, aged between 13-15, develop their creative and critical thinking and writing skills, while raising general student motivation and enthusiasm levels by making the writing process fun, in the context of working towards the FCE course.

Why conduct a long-term poetry project with teenagers?

Teenagers are at a critical stage in their development where they are generally emotional and creative in their thinking and self-expression, yet are also developing the ability to think critically using logic and reason. Therefore, teenagers respond well to activities that have a fundamental expressive, yet critical purpose. As Gordon Lewis confirms, ‘When an activity is designed so that it addresses both types of thinking [creative and critical], students strengthen valuable academic skills and stimulate their curiosity.’ (see note 2). When well-exercised over a period of time, creative and critical writing activities centred around poetry can help to promote the mature development of writing skills, even for students who are not initially as interested in poetry, providing that poems are tailored to be thematically relevant to students’ interests.

Why poetry?

Poetry as an art form exploits language and form in its entirety: everything in a poem has meaning. The beauty of poetry analysis is that interpretations and creative ideas cannot be incorrect, providing that they are shaped from logical consideration of the text and are backed up by textual evidence. This gives students the freedom of exploration, autonomy and confidence in their writing. Poems are also usually shorter than prose and can therefore be revisited many times for the discovery of new layers of meaning.

How was this project conducted?

This is a brief overview of what students were required to produce:

- 11 critical essays based on 11 poems.

- Final poem: ‘Poetry Challenge Extravaganza’, graded against the FCE writing syllabus. All students achieved results between grades A-C.

- Towards the end of the project: students wrote 2 of their own poems, which focused on a physical object or central image in depth. The poem on which they produced their best piece of writing also explored a central image in depth. The second was a collaborative class poem.

This poetry project ran during the second half of the academic year with my B2 group. We focused on one poem per fortnight. In the first week, we studied and wrote about the poem, and in the second, there was a feedback and error correction session. Half to a whole lesson or two half lessons in a week were given to studying each poem and writing an essay.

Two poetic techniques would be chosen to focus on per poem. For instance, in Jack Underwood’s poem ‘Toad’, we chose to focus on two particular poetic techniques: form and sound patterns. Analysing how the poem looks on the page and the use of repetitive sound patterns can help to reveal and emphasise an intended meaning. Focusing on sound patterns was also a useful opportunity to target pronunciation embedded within a deliberate context, such as the repetitive /ɪ/ sound, which can be difficult for Russian-speaking students to pronounce. They often pronounce /ɪ/ as the Russian ‘и’ sound, to form /i:/ or /i/ in English.

Procedure for analysing a poem and writing a critical essay:

- Build interest in the central image or theme of the poem with pictures (e.g. a toad).

OR

In pairs, answer general boarded questions related to the central image or theme (not necessarily directly related to the poem). - Present the poem on paper with a glossary.

- Teacher reads the poem while students underline any other words that they do not understand. Some students may prefer to take a flipped-classroom approach by taking the poem home to look up any unknown vocabulary. A recording of the poet reading the poem could also be played if available.

- Clarify any difficult vocabulary.

- Brainstorm ideas individually: what could the poem be about?

- Pair-check ideas.

- Students add ideas to the boarded class mind map.

- Class discussion of the poem by ‘chunk analysis’ (stanza by stanza), in relation to the set questions pre-folded back behind the poem (see note 3). These questions are answered to form the critical essay. Teacher boards students’ ideas during the discussion.

- Students write their essay in class or at home, depending on the plan. Some students prefer to take their time writing at home and others prefer to work in class under a time constraint.

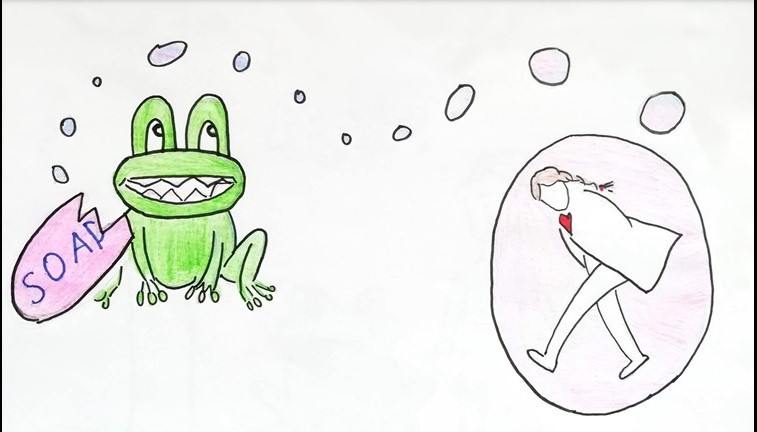

- Illustrate and present individual or group posters based on the whole or on a part of the poem. Students or groups receive the poem cut-up into sense-logical chunks and can choose a chunk to focus their illustration on. These illustrations can then be used to further develop speaking skills when presenting their own or each other’s posters.

How students approached writing their own poems:

The students’ first poem was about their most meaningful possession, as a result of not wanting to do an unmotivating writing task in the coursebook. For the second poem, students chose a mutual object of desire and all wrote a poem about the same object. In the following lesson, their challenge was to merge these poems into one collective class poem. Students collaborated to think of a first and last line to add to each other’s poems. I supported as a mediator and helped where needed. This process taught students to appreciate, take into consideration and learn from each other’s work, which also helped develop their speaking, listening, negotiation and general social skills.

Error Correction and Feedback Process

When marking the essays, I prioritised corrections to major grammar, syntax and spelling errors, which made applying corrections achievable between essays. I wrote each student’s top three strengths and corrections at the bottom of their essays and encouraged them to use the list from the previous essay when writing the new essay. When giving class feedback after handing back an essay and before writing a new essay in class, I elicited and boarded the top three collective strengths and weaknesses, as a reminder while students wrote. Then, they proofread their essays against their personal and collective lists. Students can also read each other’s work and give feedback on specific positive achievements and areas for improvement, in relation to content, communicative achievement, organisation and language.

Results

Arsenii was the youngest student in the class, yet his speaking fluency and general writing improved the most dramatically. At the beginning of the project he struggled to write a few sentences about the poems, and by the end, he started coming up with his own complex ideas that he pushed himself to develop, backed up by textual evidence. This creative project gave Arsenii the opportunity to realise his creative potential and trained him to be able to organise and express his ideas in detail.

Earlier in the project:

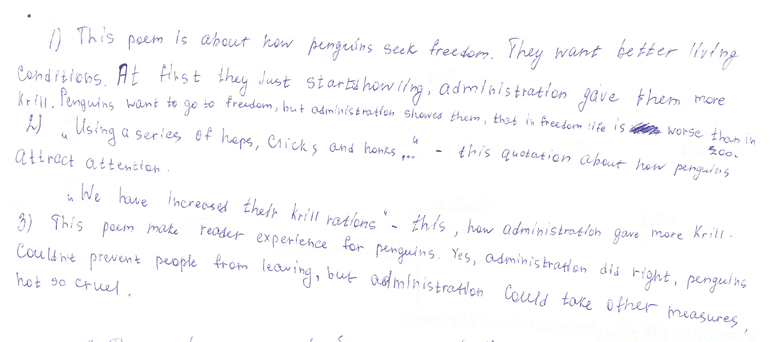

Middle of the project:

1) What is this poem about?

2) Is this poem really about penguins, or are they a metaphor and why?

3) How does this poem make the reader feel?

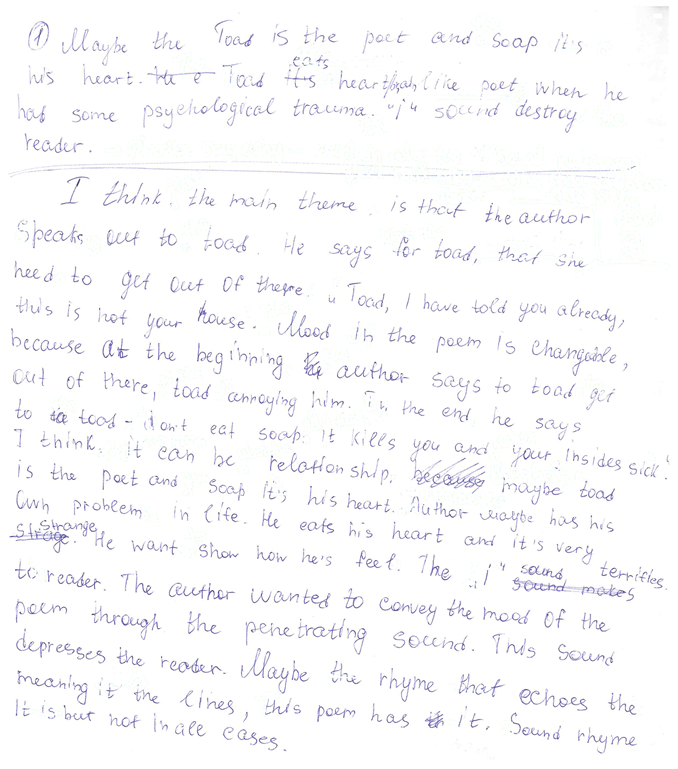

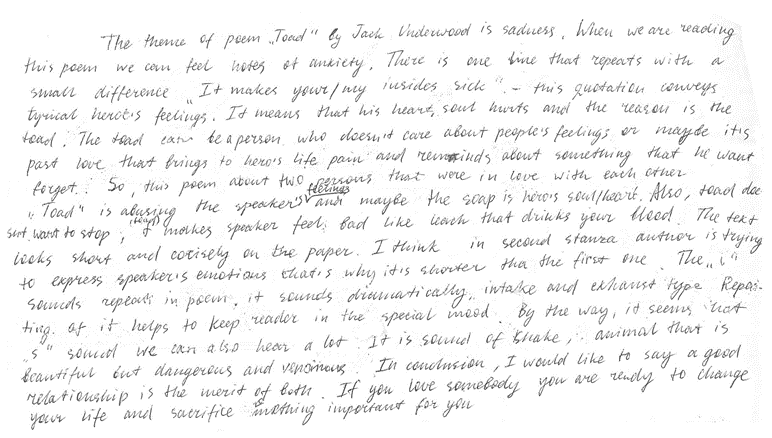

Later in the project:

Key improvements from each student (Names have been changed):

Boris - learnt to form his own opinions about a text and express them in his writing with increased detail.

Dasha - learnt to organise her ideas clearly, and explore and expand upon them more creatively and in greater depth (see note 4).

Lara - learnt to develop her own opinions about a text in greater detail and express spoken and written opinions with more ease and fluency, using sophisticated grammar structures and vocabulary.

Lilia - learnt to organise her stream of free-flowing ideas in a structured way.

Samples of portfolio illustrations based on ‘Toad’:

(own image – shared with permission of the author)

Conclusion

By the end of this poetry project, my aim for students to develop creative and critical thinking and editing skills were met. This was demonstrated through the students’ ability to analyse poetry through the application of imaginative, innovative and abstract thinking, yet using logical thinking and reasoning, assessment and evaluation in their essays, class discussions and illustrations of poetry. Not only did creative and critical thinking skills help students to improve their general writing and editing skills, but their speaking, listening, negotiation and general social skills in class. Students were able to express their emotions, opinions and attitudes with increased written and spoken fluency through this poetry project, as knowing that their interpretations and creative ideas could not be incorrect if backed-up by textual evidence, gave students the confidence and freedom to explore themselves through L2.

My other equally fundamental aim to raise general student motivation and enthusiasm levels by making the writing process fun, in the context of preparing for the FCE course, was also met. Not only is the success of this project measurable by the students’ significantly improved writing skills, but also by the students’ level of engagement with the project, their collective pride and initiative shown, which was even greater than expected. Students asked for a new poem to analyse and write about at home after class tests, when given the option of no homework, and some students also illustrated poems to decorate our class portfolio, without being asked.

A long-term class poetry project can be used to improve targeted skills to meet individual and group needs, spice up a coursebook and course content, build a creative classroom climate that can strengthen overall rapport and foster a sense of community spirit. This poetry project proves Lewis’s statement that ‘Literature is a rich source of opinion, attitude and emotion, and literary texts can be exploited in different ways to encourage learners to express their own opinions, attitudes and emotions (p. 163).

Appendix 1:

- What is the theme? Happiness?

- What is the mood of the poem? What words or phrases create this mood?

- Who is the poem about and what is the relationship between the subject and the speaker (poetic voice)?

- Think about the way the poem looks on the page: the shape, where the lines end, line length, etc. How does this influence the meaning?

- Notice the repetitive ‘i’ sound. How does this make you feel as a reader? In what ways can these sound patterns contribute to the meaning?

- Is there any kind of rhyme in this poem, even if not obvious? Think about sound patterns aside from the ‘i’ sound in question 5.

Appendix 2 - Dasha's essay:

Appendix 3:

Extra activities:

1. Create different types of exercises from each poem:

- Use fewer poems to see how many exercises can be created from each poem.

- A cut-up version of the poem could be given out before being shown in its original form, for students to reorder in groups according to what they think the logical progression should be. Then, in different groups discuss their reasoning and how the meaning of the poem might be different between groups, depending on how it has been reordered. Individuals or groups could take a photograph of their version of the poem and revisit it once they are familiar with the original form, for the purpose of comparing and contrasting any similarities, differences or changes in meaning.

- Assigning different parts of the poem to different individuals or groups to read aloud or write about.

- Writing their own poem in response to the whole poem, or to an area of interest within the poem.

- Creating a performance of the poem (possibly with costumes and props).

- Rewriting exercises (changing or adding to a poem): how would they rewrite the poem to express the same message? Would they use the same language (further explore or play with pre-existing language, i.e. wordplay), form (shape, line length, enjambment, stanza order, meter, rhyme), sound patterns, imagery, tone, genre, context, point of view (poetic voice or another subject’s)? What would they ‘keep, change, add, remove’? Why?

OR

Rewrite the poem using the same key images to express a personal or social problem that affects teenagers today, by exploring the same poetic techniques in a different way or using different poetic techniques. - Language awareness prediction exercises: remove words and encourage students to consider the overall message by using surrounding language and tone, in order to work out the words or choose their own words to fill in the gaps. This task would be useful practice for FCE Use of English.

2. Focus on editing skills:

- Read and make suggestions about each other’s work using purposeful guidelines set by the teacher.

- As the project progresses, introduce word counts to encourage shorter and more concise essays, as part of exam preparation technique training, for the purpose of focusing in more depth on a key idea and considering language quality.

- Create exercises using students’ essays: detailed expansion of a word count or to work on paraphrasing skills and reducing a word count.

3. Explore what is not in the poem: what it might mean if there is no clear set meter or rhyme, instead of it being another element less to consider, or dismissing the poem for being of a contemporary genre.

4. Read and engage with reviews of the poem or poetry collection in which the poem appears: after students have explored their own ideas through the essay writing process, they could read a review for the purpose of being exposed to other interpretations of the same poem and to write an engaged response. There could be an example of a positive and negative review, to which students can write an opinion piece to support or argue against the reviewer’s opinion. This is also extra exposure to other authentic materials of different writing styles in relation to the class poem.

5. Focus on grammar and collocations: teaching grammar in a creative context or teaching grammar creatively, such as by using the poem to teach or revise a grammar topic from the coursebook.

Footnotes

1 Michael, Lewis, ‘Classroom Reports: Using Poems and Songs in a Lexical Framework’, in Implementing the Lexical Approach: Putting Theory into Practice (Hove: Language Teaching Publications, 1997), p. 163.

2 Gordon, Lewis, ‘Chapter 2: Creative and Critical Thinking Tasks’, in Resource books for teachers: Teenagers, ed. by Alan Maley (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), p.43.

3 See ‘Appendix 1’ for the questions written for Jack Underwood’s poem ‘Toad’.

4 See ‘Appendix 2’ for Dasha’s essay answering the questions in response to ‘Appendix 1’.

|

References Lewis, Gordon, ‘Chapter 2: Creative and Critical Thinking Tasks’, in Resource books for teachers: Teenagers, ed. by Alan Maley (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 43-77 Lewis, Michael, ‘Classroom Reports: Using Poems and Songs in a Lexical Framework’, in Implementing the Lexical Approach: Putting Theory into Practice (Hove: Language Teaching Publications, 1997), pp. 162-172 Underwood, Jack, ‘Toad’ in Happiness (London: Faber & Faber, 2015) p. 12 Where to find poetry online: Poetry Foundation - https://www.poetryfoundation.org/ Poetry International - https://www.poetryinternational.org/pi/home Poetry Society - https://poetrysociety.org.uk/ National Poetry Library - https://www.nationalpoetrylibrary.org.uk/ Poetry magazines of internationally respected contemporary poetry: Poetry Wales - https://poetrywales.co.uk/ Magma Poetry - https://magmapoetry.com/ Glossary of poetic terms: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/learn/glossary-terms An accessible contemporary book about reading and writing poetry: Falley, Megan, and Andrea Gibson, How Poetry Can Change Your Heart (Chronicle Books: San Francisco, 2019) Poetry analysis for British state school exams: BBC Bitesize GCSE WJEC: Writing and Analysing Poetry - https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/topics/zxyh6fr |

Author's bio: Keely Laufer finished her BA in English Literature and Creative Writing at Aberystwyth University in West Wales, followed by an MA in Creative Writing: Poetry, at the University of East Anglia in England. She then completed her Cambridge CELTA at International House London, followed by specialisation training at International House Moscow: 'IH Certificate in Teaching Very Young Learners, 2-7yrs', 'IH Certificate in Teaching Young Learners and Teenagers (IHCYLT)' and the 'IH Certificate in Developing literacy skills with primary and pre-primary learners'. She is particularly interested in stimulating a creative classroom climate through storytelling and craft projects for VYL, literacy projects for YL, and through running poetry courses to develop critical and creative writing skills in higher level teenagers.