China: the before and after

By Jacqueline Douglas and Rosie Edge

By Jacqueline Douglas and Rosie Edge

With a population getting on for 1.5 billion, while it may be remarkable that some 400 million are English speakers, that leaves approximately three quarters of China as a substantial ELT market. There is even an English language teaching outfit that is the world’s largest even though they only operate in that one country. Having been teacher training there recently, for General Plan IH Shanghai, we would like to report on what we have seen. This article has a twin focus, a before and after in two senses. First, the difference observing English lessons in state schools now compared to ten years ago and then exploring the benefits of a training formula that bookends input either side of in-school observation.

The first thing to say is: do not be fooled by the blackboard and chalk in classrooms. Rather than being a hangover from the past, this is a deliberate choice. It is appropriate in the 21st century as it is more easily seen from the back of a large classroom than a whiteboard would be and does not preclude the use of an interactive whiteboard. This photograph shows one of the authors with the typical arrangement in the schools now – a double blackboard, one half of which slides smoothly across to reveal a screen connected to a projector.

The first thing to say is: do not be fooled by the blackboard and chalk in classrooms. Rather than being a hangover from the past, this is a deliberate choice. It is appropriate in the 21st century as it is more easily seen from the back of a large classroom than a whiteboard would be and does not preclude the use of an interactive whiteboard. This photograph shows one of the authors with the typical arrangement in the schools now – a double blackboard, one half of which slides smoothly across to reveal a screen connected to a projector.

Back in 2008, English lessons were typically teacher-centred, a presentation followed by language practice: students repeating what the teacher said, with little or no time to experiment, no time to have a go and get it wrong on the way to getting it right. You might even have seen a teacher asking a pupil to stand up, coursebook in hand, and recite from the grammar reference at the back. It was enough of a challenge to encourage teachers to increase student-centred time in a forty-minute lesson by five minutes, from say 10 minutes to quarter of an hour.

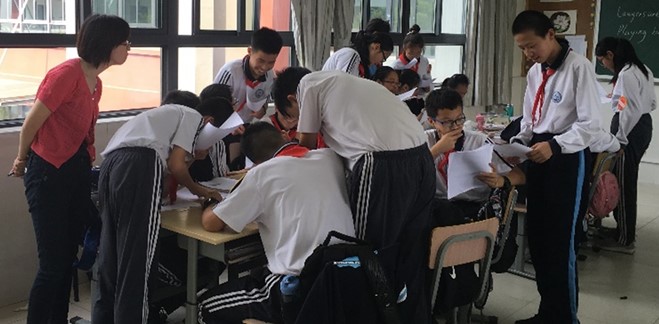

What a difference a decade makes: it is the same classroom, there are still up to 50 pupils in there, but here are the wonderful developments. The coursebooks are better – now all is in English except at times the rubric, and the English is natural. The furniture might well be arranged as tables in islands, and even when there are still rows, students are clearly used to working in groups, pairs turning around on cue to do tasks with those behind. They know who their group mates are, there are group leaders and these not only perform the role of teacher’s assistants in a large class, but with a signal they go to ‘spy’ on another group mid task to compare answers. In this way, there is evidence of dual-level training: the teachers have been trained in communicative language teaching (CLT) and in delivering student-centred lessons, no longer mystified as to how they might go about it – and how to control what they envisaged would be ensuing chaos. Then at the other level, they have in turn trained their pupils in a new way to behave in class, a new way to work and learn. Furthermore, as we were training teachers to do something new to them, for example process writing with peer evaluation checklists that were too wordy, when they are then training their students, for whom this is also new, they will have empathy if it does not go perfectly the first time. This is in wonderful contrast to CELTA where we see unskilled teachers teaching skilled students.

In 2008, one pioneer teacher who managed a wonderfully-noisy lesson with group speaking tasks said she had been up all night planning it and was worried the headmaster might complain about the noise. Fast forward to 2019 and student-centred learning is now the new normal and the standard of teaching is higher: we see the approaches familiar in our classrooms when we teach. Language is contextualised, the context often being meaningful with personalisation and localisation, and the lesson beginning outside the coursebook. There is guided discovery and differentiation, and the better teachers adapt material to include more speaking. Work on reading can often focus on developing rather than testing: in graded language the teacher checks the reading task type by asking if pupils will read quickly or word by word and in pair checks and feedback, will focus on evidence in the text for the right answer.

Classroom management has leapt forward: the teacher in this photograph is not untypical – she does manage to monitor with that many in her class, and there is less ‘time’s up’ after a task has been running for forty seconds, so the pace is more student-led. When we comment to GPIH’s Simon Cox on seeing this evidence of training, he says ‘we’re proud to have been involved in such a big change’. We readily agree, partly since those pupils working around islands then move the tables back into rows as the lesson ends – ready for the maths/science teacher, so it is for the English class and does not seem to be a top-down, school-wide development. We know that GP has signed and renewed contracts with the country’s Education Bureaux. This may have filtered down via an older colleague of our cohort trained in the interim years.

Classroom management has leapt forward: the teacher in this photograph is not untypical – she does manage to monitor with that many in her class, and there is less ‘time’s up’ after a task has been running for forty seconds, so the pace is more student-led. When we comment to GPIH’s Simon Cox on seeing this evidence of training, he says ‘we’re proud to have been involved in such a big change’. We readily agree, partly since those pupils working around islands then move the tables back into rows as the lesson ends – ready for the maths/science teacher, so it is for the English class and does not seem to be a top-down, school-wide development. We know that GP has signed and renewed contracts with the country’s Education Bureaux. This may have filtered down via an older colleague of our cohort trained in the interim years.

To explore those training programmes, we turn to our second theme: the power of in-country in-service training that offers input-teaching practice-input. Alongside the tutor-observer are local colleagues who are fellow course participants and the format becomes a delicious ‘sandwich’ with these benefits:

- they know their observer a little.

- in input, they can see their tutor managing a class and demonstrating methodology, so we put our money where our mouth is and as observers we have credibility .

- the tutor sees their personalities in the initial input sessions and this helps to see how they are in their lessons, their teaching persona, does their character come through?

- the second tranche of input is relevant, based on their classes so that 1) content is tailored, 2) it might carry more weight since they know you have seen them in their context, and 3) there is sharing by course participants of what they had seen a colleague do.

- one example of this tailoring is that having commented on the line ‘so much for that’ by several teachers to close carefully-prepared lessons, we found they were surprised that no-one had told them before. They then requested input on teacher language, and we were able to deal with such verbal ticks as the abrupt ‘yes or no’ and ‘s’down please’. We helped them to see they can offer graded language that is succinct and clear without being strict – the best of a Chinese directive style with smiles and a softer tone. There is a clue as to whether or not this will be effective in the progress of teachers on another GPIH course, where there was clear response to feedback to a previous lesson in which teachers had been told to sound friendlier. Tailoring input additionally allowed us to unveil the reason some teachers avoid monitoring at the back of the room - because ‘that is where the trouble is’ and in a busy lesson, there can be reluctance to deal with weaker students.

Being in their environment also allows us to see the ‘same’ lesson by different teachers with different classes and then in feedback discussing the choices they had made. The fact that they share the same context and experiences means that we know roughly what to expect, too. In this case, they are good observers. Even when one of us had forgotten to bring observation task sheets, they were just as good in feedback having watched well and made pertinent notes anyway. This being the case, we wonder if use of the Chinese Wechat could work well in the same way that we have been using chat software such as Slack/Flock/Whatsapp in CELTA TP elsewhere. Moreover, we were not dealing with emotions so much: the teachers were not stressed with being observed, since they are videoed 2 or 3 times per semester in a special room with full camera set up. We can also be realistic and forgiving knowing they might not always offer CLT when we are not there to observe. As one teacher put it ‘students enjoy it when observers are coming because they know they’ll get an enjoyable and active class’, because of the additional lesson preparation. If our message is ‘teaching does not equal learning’ and that students may not ‘get’ the present perfect after we have taught it, then why should we as trainers expect trainee teachers to go away and immediately adopt new methodology all the time?

Being in their environment also allows us to see the ‘same’ lesson by different teachers with different classes and then in feedback discussing the choices they had made. The fact that they share the same context and experiences means that we know roughly what to expect, too. In this case, they are good observers. Even when one of us had forgotten to bring observation task sheets, they were just as good in feedback having watched well and made pertinent notes anyway. This being the case, we wonder if use of the Chinese Wechat could work well in the same way that we have been using chat software such as Slack/Flock/Whatsapp in CELTA TP elsewhere. Moreover, we were not dealing with emotions so much: the teachers were not stressed with being observed, since they are videoed 2 or 3 times per semester in a special room with full camera set up. We can also be realistic and forgiving knowing they might not always offer CLT when we are not there to observe. As one teacher put it ‘students enjoy it when observers are coming because they know they’ll get an enjoyable and active class’, because of the additional lesson preparation. If our message is ‘teaching does not equal learning’ and that students may not ‘get’ the present perfect after we have taught it, then why should we as trainers expect trainee teachers to go away and immediately adopt new methodology all the time?

Our conclusions are that English teaching in China is definitely going in the right direction and that the input-observation-input format has benefits that input-only courses, which a teacher may leave their country for, do not. Is there a case for more in-country training or courses with a follow-up option of observation or mentoring?

Author's bio: Jacqueline Douglas is a freelance trainer September to March and teacher/ trainer at Bell Cambridge April to August. She has 20+ years’ experience in ELT, in the UK, Turkey, Spain and Bolivia and training in China, south east Asia, South America, Egypt, Greece, Russia, Sudan and Saudi Arabia. She is a CELTA and Delta tutor, and trains in CLIL, train-the-trainer and evidence-based teaching. Jacqueline has an MA from NILE, focussing on materials development and learner autonomy, and is a regular speaker at conferences including IATEFL. Blog: jacquelinethetrainer.wordpress.com

Author's bio: Rosie Edge spent ten years teaching in South America before moving into teacher training in 2010, working on CELTA courses in Colombia and Mexico. Since becoming freelance in 2013, work has taken her eastwards into Europe, the Middle East, India and China. She has moved professionally into ICELT as well as working with local teachers in their own contexts in China, Malaysia and Jordan.