Creating a can-do attitude in students

By Raul Pope Farguell

In 2018–2019, BKC-IH Moscow launched an initiative, Focus on the Client. It set out to offer value for money as a business and academically to make learning more effective. As a result, it adopted promoting learner autonomy and making lessons more student-centred as objectives. These newer objectives sat alongside the existing objectives of maximising student retention and increasing student satisfaction.

One of the proposals was to use Can-Do statements in our classes and below I’ll detail what Can-Do statements are, how we envisaged them in our context, and how we trained our teachers to use them. Then I’ll describe how feedback was collected and what teachers had to say about their experience, before finally adding what we have done since to advance their use in the school.

Background to can-do statements

Can-do statements, as a term, may sound vague and unfamiliar, but in fact make up the backbone of something very well known: the Common European Framework Reference for Language (CEFR). The CEFR segments language proficiency from A1-C2 and even further into Basic User (A1-A2), Independent User (B1-B2) and Proficient User (C1-C2). Despite not intending to be prescriptive, the CEFR and the corresponding levels make up a ‘conceptual grid’ of language competence (Council of Europe, 2001).

To illustrate how they are written, above is a selection of the descriptors for A1, B1, and C1:

|

A1 |

Can understand and use familiar everyday expressions and very basic phrases. Can introduce him/herself and others and can ask and answer questions about personal details such as where he/she lives. |

|

B1 |

Can understand the main points of clear standard input on familiar matters regularly encountered in work, school, leisure, etc. Can deal with most situations likely to arise while travelling in an area where the language is spoken. |

|

C1 |

Can understand a wide range of demanding, longer texts, and recognise implicit meaning. Can express him/herself fluently and spontaneously without much obvious searching for expressions. |

^ Source: Council of Europe (2001)

These are further broken down when describing skills, but perhaps more importantly, are used in coursebooks such as Empower, Alter Ego+, and Nuevo Español en Marcha, to describe the objectives of the different units.

Rationale for using can-do statements

As stated above, choosing to use Can-Do statements was to achieve certain organisational aims: student satisfaction and retention, promoting student autonomy and student-centred classrooms.

The use of Can-Do statements was to primarily foster student recognition of their own learning and progress while studying since it was a common complaint that progress went unnoticed after a certain time. The Can-Do statement would therefore frame a lesson’s objective and be the basis of feedback at the end of the class for the students to self-assess to what extent they had achieved the lesson’s aim(s).

The aim was to be phrased with the communicative purpose of the lesson at the fore, and could, if the teacher wanted, include the grammar. For example:

- Describe a recent holiday using the past simple.

- Discuss your family, lifestyle, work and education using expressions with go.

- Request information about a course using informal English in an email.

- Give feedback on a peer’s for and against essay.

- Compare Moscow and other world cities using comparatives and superlatives.

Setting up the trial and the scheme

The first step was to ask for volunteers to try something new in their classrooms. We used the school’s mentoring system to encourage mentors to approach their mentees about the trial. We held a training session explaining the benefits to the teachers and the students, most of which are outlined above, but also included being able to plan with a greater focus on what the teacher wanted the students to be able to do by the end of the class, making connections between a student’s reasons for coming to class and what would be the focus of the lesson, and then conducting feedback by relating back to the aim(s) of the lesson.

The first step was to ask for volunteers to try something new in their classrooms. We used the school’s mentoring system to encourage mentors to approach their mentees about the trial. We held a training session explaining the benefits to the teachers and the students, most of which are outlined above, but also included being able to plan with a greater focus on what the teacher wanted the students to be able to do by the end of the class, making connections between a student’s reasons for coming to class and what would be the focus of the lesson, and then conducting feedback by relating back to the aim(s) of the lesson.

The session additionally focused on explaining the nature of Can-Do statements, providing examples and then a practical phase of looking at the coursebooks we use and crafting Can-Do statements for those pages. It was a chance to field any questions the teachers had, one in particular being about the right quantity of statements per class. For our trial we understood that given the varying lengths of a lesson, a class may well have more than one objective, which is subsequently reflected in the number of Can-Do statements. Finally, posters were created summarising the information and included the types of vocabulary, grammar, listening and reading texts, also speaking and writing tasks.

Having received favourable reviews from participants a month later, the training session was repeated as an elective workshop at our monthly seminars. Some of our other longer-term objectives were to include Can-Do statements as part of the criteria for formal observations and monitor student feedback for references to their use. We planned two data collection points in January and May.

Having received favourable reviews from participants a month later, the training session was repeated as an elective workshop at our monthly seminars. Some of our other longer-term objectives were to include Can-Do statements as part of the criteria for formal observations and monitor student feedback for references to their use. We planned two data collection points in January and May.

The feedback

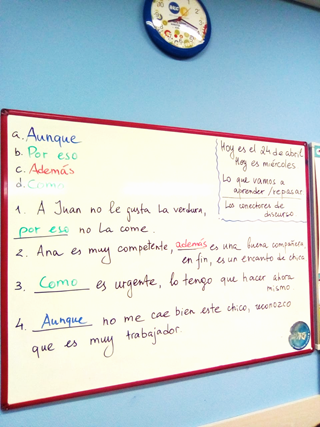

Using an online questionnaire to collect feedback, a link was distributed through mentors, the weekly newsletter and by myself to anyone who I knew had been using them. I was taken aback by some of the responses, since I didn’t only receive reviews that some had enjoyed using the statements while others had had difficulties, I received photos of boards and explanations of how the usage of the statements had evolved as the year went on. See Figures 1 and 2.

In the questionnaire I encouraged the respondents to share their experiences and suggest improvements going forward. Their replies are below and ordered according to the questions asked in the questionnaire.

Question: How have can-do statements made a difference to your teaching?

- “My lessons are more organized. I can see clearly what our goals are. They’re quite useful at the end of the lesson. They help to reinforce everything that’s been learned.”

- “They helped me structure my lessons with teens and some adults. It also helped to manage expectations and demonstrate progress.”

- “I think it’s made me more mindful and aware of my teaching aims, both in terms of the micro-level lesson planning.”

- “I’ve only really used them with English File/ adults.”

- “It’s not so easy to understand if the aim has been achieved. It doesn’t feel natural to use them in feedback for me.”

Question: Do you have any comments for teachers considering using them?

- “Do use them! They show that you’re ready and well planned.”

- “I’ve loved adding this little ritual to my teaching.”

- “I wonder how easy they’d be to use if you’re asked to do a last-minute cover.”

- “Be brief. Use the ones in the books if you want.”

Conclusions and recommendations

Overall, the feedback was positive and the feedback that raised questions and doubts was at least constructive and will inform future training. In total, twenty-five teachers responded to the survey and 85% said they were likely to carry on using the statements. BKC-IH Moscow is a sprawling school with over 300 teachers, so there are still plenty of teachers to reach.

The biggest plus from the responses is how beneficial teachers found the statements when planning and structuring their classes. This was a reoccurring theme and is perhaps the logical starting point if you’re asked to consider how something has influenced your teaching. An interesting case is one teacher commented on how they used the statements during the lead-in to explicitly draw the students’ attention to the objectives of the lesson, while another said although their younger students didn’t seem to notice the statements on the board, the parents enjoyed knowing what was going to be studied.

The most notable thing to be addressed is the way the Can-Do statements are referred to at the end of the class for feedback. As a comment above signifies, structuring feedback around the aim of the lesson needs unpacking and wasn’t something demonstrated in the training seminar. Likewise, the sessions were given with adults in mind and how they can be adapted for (V)YLs is something to include going forward since more than half of our students are under 18.

That being said, there have been two recent developments for better feedback and YLs. Figure 3 is of a teacher’s board who writes, ‘What did you learn?’, ‘What do you think?’ and ‘What did we do?’ on the board for feedback for their pre-teens class. Another teacher, who teaches teenagers, uses exit slips to ask similar questions, but adds how the lesson benefitted them, directly relating back to the students’ personal, language-learning goals.

It is clear from the above that teachers have found the scheme beneficial, especially for their own teaching and focus. However, the training didn’t make enough of the practicalities of using the Can-Do statements for feedback and how to carry it out. Ultimately, this is why there was less of a focus on feedback than incorporating Can-Do statements into classes. Going forward, future sessions will favour conducting feedback and fostering student reflection.

|

References: Council of Europe (2001). The Common European of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge: CUP. |

|

Author's bio: From Poole in the UK, Raul Pope Farguell is the Assistant Director of Studies for Modern Languages at BKC-IH Moscow. He has experience teaching in Japan, China, Spain, Italy and the U.K. and is also a CELTA trainer and Trinity examiner. |