Creative speaking – Storytelling to learn to speak

By Maria Conca

Storytelling, along with Creative Writing, has become very popular in ELT practice in recent years. Possibly, this is because creativity is everywhere and seems to be a benchmark to measure learner-centred teaching practice (Richards, 2013). Particularly, Storytelling has become for some practitioners a teaching method; others still consider it a classroom resource or a performative activity.

While I was teaching another storytelling course to YLs, I had an epiphany. I had noticed that my young learners had significantly improved their writing during a storytelling course, in which they had been exposed to stories told by myself or recorded storytellers from various sources.

For each story, taught in stand-alone lessons, I had designed and used a series of activities to get YLs motivated to listen again, understand further details, interpret and imagine how the events unfolded. They then had to think about what happened next, what would have happened if things had gone wrong or just differently, how they could have changed the storyline to re-write, end or continue the story. All these discussions led to a fluency activity in which I asked learners to re-tell the story using prompt cards showing words or chunks extracted from the original text. As a variation to that, I often asked learners to create or just re-invent the story using different prompts of their choice or from a given set.

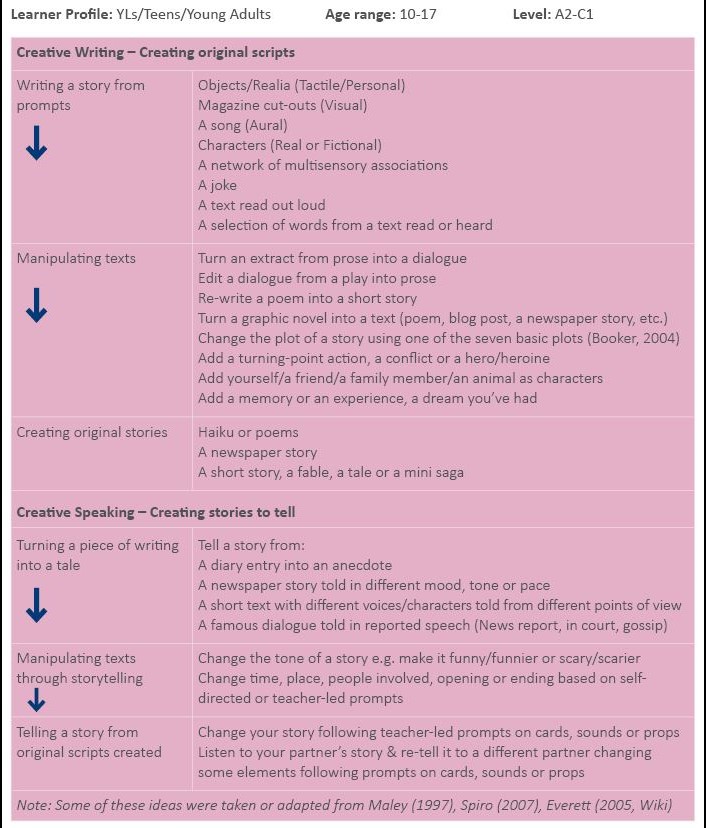

When asked to re-invent the story, it was inevitable for them resorting to writing first. Written prompts, plenty of time and some creative writing techniques were crucial to prepare for great storytelling. Well, the results were incredible: learners were able to recycle vocabulary and chunks from the original input and seemed to handle textuality and language structures more naturally. It looked as if oral fluency had fed into written fluency and the other way around. I wondered: why can’t a Creative Writing task turn into a Creative Storytelling activity that fosters language use while shifting the output mode from written to oral? All I had to do was give it a try. There were some issues to be taken into consideration though, for which I had some possible solutions (see table overleaf).

Creative Speaking stems from a Creative Writing task, in which learners will first create a story to tell from prompts of different kinds (visual, aural, tactile, multisensory, personal, etc.) set in a clear

Creative Speaking stems from a Creative Writing task, in which learners will first create a story to tell from prompts of different kinds (visual, aural, tactile, multisensory, personal, etc.) set in a clear

context or inspired by a negotiated theme. The teacher will employ process and collaborative writing techniques leading to an individual piece of work so that everyone is involved and feels entitled to give that personal touch to the final product that makes each story unique and interesting to tell or listen to. When does storytelling become ‘creative’? How? By adding characters, twists & turns, props, shifts in time or place, a change of mood/tone selected by the teacher beforehand. These can be omitted features of a pre-existing story or just new elements, which learners will gradually integrate into their storytelling. Learners will have to adapt to the unpredictable creatively, and resort to their language resources to avoid a breakdown. How does Creative Speaking help improve fluency, accuracy or self-confidence? I’ll give a brief account of what research says in the next paragraph.

How Creative Speaking Promotes Fluency, Accuracy & Self-confidence

If Storytelling is ‘the art of narrating a tale from memory’ (Dujmovic, 2006 p.1), Creative Speaking is the moment when memory fails or some unpredictable elements come up and creativity steps in. Creativity is a problem-solving exercise that increases learners’ levels of motivation and self-esteem (Richards, 2013). In Storytelling, the delivery is crucial, as it often is a performance requiring rehearsal and preparation (Dujmovic, 2006). As learners take up the role of a performer with a real or imaginary audience, storytelling clearly provides a motivating context for learning, especially for YLs. Rehearsals and preparation offer the opportunity to learn to perform in a low-anxiety environment, in which, however, there is still room for repair or improvisation. Researchers and practitioners claim that storytelling enhances language learning by ‘enriching learners’ vocabulary and acquiring new language structures’ (ibid.), in this respect it can promote accuracy. Creative Speaking uses rehearsed storytelling as a springboard for non-rehearsed, spontaneous talk that may spark from the unpredictability of real-life communication. It is a realistic, fluency activity that fosters flexibility, adaptability and the ability to use language resources effectively. Creativity can ‘rekindle’ interest (Richards, 2013 p.2) and avoid demotivation or lack of engagement. All learners are ‘capable of some degree of creativity’ (Maley, 2007 p.8) if tasks require an individual contribution to them.

How can we elicit learners’ creativity in the language classroom? Richards (2013) quoting Maley (1997) says that the use of ‘a variety of different literary and non-literary sources’ elicits ‘creative thinking and behaviour’. It develops the ability to discover, invent, ‘find new ways of looking at what is familiar’ (Maley, 2007 p.8) and make ‘creative connections’ (Richards, 2013 p.2). The key here is ‘creative’ not the language ability or the process the task will focus on, e.g. speaking vs. writing, expressing vs. thinking. Tasks with ‘creative dimensions’ (ibid.) facilitate language learning. These tasks involve ‘open-ended problem solving’ (ibid.), which can adapt to the learner’s response in terms of individual choice, flexibility and personal content. Such tasks require learners to express their own imaginative world by adding their original thoughts and ideas to others’ or their own stories. A continuum of fantasy and creative language use require challenging, intriguing tasks, with a novelty element that will engage with its contents. In the next paragraph, you will find an overview of lesson ideas and activities for Creative Speaking.

Practical ideas

Conclusion

Interaction-based and open-ended elements in the language classroom can help learners cope with unpredictable real-life communication. Tasks that trigger learners’ creativity are crucial for language learning and the acquisition of skills that they will need for the future (Richards, 2013). Creative Speaking as an extension to Storytelling and/or Creative Writing seems to be a feasible option to make learning more enjoyable and your teaching more learner-centred.

Author's Bio: Maria has been teaching English for over 11 years in the UK and in Italy, where she’s based and has been running her self-owned language school since 2011. She took her CELTA at IH Rome in 2007 and completed her Delta at IH Newcastle and Distance Delta IH London in 2016. She works a Teacher, CLIL & Primary Education Teacher Trainer, DoS, Senior Academic Manager, Course Designer & Consultant. Her main interests are YLs, Teaching Listening & Speaking, CLIL, Second Language Acquisition (SLA) and ELT materials development. She tweets at @MConca16.

|

References: Booker, C. (2004). Seven Basic Plots. Continuum Dujmovic, M. (2006). Storytelling as a method of EFL teaching. Available online https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/17682 - Retrieved on 28/09/2018 Everett, Nick. (2005). Creative Writing and English. The Cambridge Quarterly. 34 (3):231-242 Everett, Nick. Creative Writing Wiki. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Creative_writing Maley, A. (1997). Creativity with a small ‘c’. In Clyde Coreil (ed.) The Journal of the Imagination in Language Learning and Teaching, 4. http://www.njcu.edu/cill/journal-index.html - Retrieved on 28/09/2018 Richards, J. (2013). Creativity in Language Teaching. https://www.professorjackrichards.com/wp-content/uploads/Creativity-in-Language-Teaching.pdf - Retrieved on 28/09/2018 Spiro, J. (2007). Storybuilding. Series Editor Alan Maley, OUP |