Tracking Teacher Development

by Tim Brombley

Three years ago I made a small change to the Professional Development system at IH Bydgoszcz to make it easier to follow up on observation feedback in subsequent observations. The impact it had was, I believe, as positive as I had hoped it would be for our teachers, but it had some wonderful and far-reaching repercussions that I had not originally planned, including the creation of a list of developmental objectives for new teachers.

Why change the system at all?

As a teacher, observations were always something I looked forward to and the feedback was always perceptive and interesting to receive. The detailed notes and the general comments the observer provided always got a second reading at a later date (or repeated readings if there was anything particularly glowing) and I always decided to make changes to classroom practice based on the recommendations or criticisms that were made, regardless of whether those changes were actually made.

That said, there was always a sense that this was all a bit piecemeal, and there was often little or no follow-up in subsequent observations. If there was any, it came by dint of the fact that the observer was the same as last time, and on those occasions feedback put in the context of previous performance always had more meaning.

Having it pointed out that something we are doing well is something we have previously done poorly gives food for thought on what has changed, and how that change came about. Similarly, a comment that something done poorly is something which has previously also been picked up on helps us to avoid dismissing it as a glitch; it is harder to say, “Yes, yes, but usually I don’t do it like that,” in the face of evidence that we have been seen doing it before. Conversely, failing to concept check in an observation when you have previously been commended on rigorous and effective concept checking allows you to see that this is probably not a systematic error in your teaching, and reflect on it accordingly.

Perhaps less obviously though, and yet more importantly in the long run, what I had previously been missing was a way to actually keep track of useful comments and decisions so they wouldn’t get lost; some way of recording it all in one place so that it was easily available. In short, a way to manage my professional development.

What was the change?

With a vague sense that we’d benefit from managing individual professional development better, I decided to pilot a simple change in our school’s lesson observation procedure. At the time, our observation procedure was as follows:

- Pre-observation, the teacher provides a lesson plan and a cover sheet outlining lesson aims, personal aims, expected problems and planned solutions, and copies of any materials being used.

- During the lesson the observer takes detailed notes on a prepared (but effectively blank) sheet.

- Post-observation, the teacher completes a ‘Hot Feedback’ form with their immediate thoughts on the lesson.

- In the feedback session we discuss the teacher’s and observer’s feedback and agree areas for further professional development. The teacher receives the detailed notes and a general summary of the lesson, and a copy of everything is put on file.

The change I wanted was to make it easier for observers and teachers to see, over the course of a year or two, what observations had been made, and what weaknesses had been turned into strengths. Apart from anything, it’s motivating to see such progress in black and white, but it also increases the desire to focus your own efforts when you know that your areas to work on will be reviewed later and any progress will be noted.

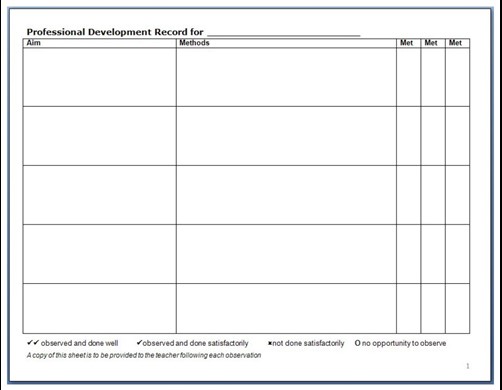

So, being a believer that the purpose of well-designed paperwork is to help us do our jobs better, I set about creating a simple record sheet onto which professional development aims would be written, shown below. Being geared towards supporting lesson observations, there is a column for aims, and one for recording what a teacher could actually do in a future observation to show that that aim has been met. There are also three columns to tick each aim or method as met in three subsequent observed lessons.

And that was it. Except it wasn’t, of course: it was pilotted in a few observations, some amendments were made, and then the change and its rationale were explained to senior staff and then to teachers, before implementing the change across the school. In essence we amended step 4 above to the following:

4. In the feedback session we discuss the teacher’s feedback and the observer’s feedback and write any areas for further professional development in the PD record. The teacher receives the detailed notes, the PDR and a general summary of the lesson, and a copy of everything is put on file.

Not a major change, then, and not a lot more workload, since completing the record simply became the physical outcome of the existing task of deciding or agreeing areas for further professional development.

Several people have asked who it is who decides what goes in the form, and the easy answer is: it depends on who is using it. Personally, working with experienced teachers I am more likely to end a feedback session by asking what the teacher would like to add to their PD record, while with newer teachers we are more likely to be directive more of the time.

There is also the question of when previous aims are ticked off as ‘met’, and the answer is the same: it’s a decision based on what works best for the people involved. It may detract from the ability to observe with an open mind if sitting in an observation with what is essentially a checklist, but other than that we have found that checking things off before or during the feedback session are both effective.

Benefits: ease of follow-up

As I’ve said before, a good piece of paperwork helps us to do our jobs better, and there were a number of unplanned benefits.

Firstly, having to complete the form meant that for each observation both the teacher and the observer revisited the essence of all previous observations. Clearly, there is a lot to be gained from this, but one might argue that people could do that already by revisiting their previous notes and previous summaries. That is true, but not everyone has either that much discipline (I put a hand up to that one!) or enough time to go through all that text (pause in typing while I raise both hands). Also, even if you had all that time and discipline, why would you look at last year’s observation paperwork if there is no record of which comments are still needing action? So, the Professional Development Record became a quick and informative review to focus our attentions before observation or before feedback.

Benefits: consistency of feedback

Breaking our development goals into aims and methods (observablebehaviours/outcomes) made us consistently give concrete advice supported by a rationale, or, if you want to look at it the other way round, clear objectives supported by observable ways to achieve them.

This meant that in cases where we could give a teacher a clear aim, such as “Increase lesson pace with a variety of feedback activities” for a teacher whose lessons were dragging due to singular reliance on teacher-centred, open-class feedback, we were forced not to simply leave it at that, but to provide the teacher with ways to achieve the aim, so this became:

| Increase lesson pace with a variety of feedback activities |

|

Benefits: coherent feedback messages

We felt that it was best not to give more than 3 new goals based on one observation, but there are often a number of little problems which you don’t want to not address. However, when you step back a bit, many of these little things are actually connected in some way, and when presented under a single aim, actually form a coherent and manageable message.

For example, we had a teacher who sat her students in a horseshoe so close to her that, wherever she turned, she had her back to one third of them, and as a separate issue she also spent more time than was desirable writing planned input up on the board. In this case we saw that, while the first problem affected engagement of students through not being able to make eye contact and the second problem mainly affected pace through students being unoccupied while the teacher wrote on the board, both involved the teacher having her back to students and affected engagement. As a result, the one aim with its two methods became:

| Increase time spent physically engaged with students |

|

Benefits: a developmental plan for new teachers

Effectively, by gathering our feedback in one place it had become very easy to get a school-wide perspective of what our teacher training goals should be, based upon our teachers’ actual performance. So when, after a year, we realized that we were often saying the same things over and over, we reviewed all of our records and put together the most commonly listed feedback messages. This we then gave to all teachers in their first two years with the school and let them know that these were the areas that we would be looking to see them demonstrating competence in as a matter of priority.

The content of this 1st– and 2nd-year development record may be of interest to you, but you may also disagree with what we have identified as key areas for early development—that’s fine: it is not exhaustive, nor is it an attempt to encapsulate the essentials of teaching on one side of A4. Rather, it is in essence simply a collection of high-frequency feedback comments from IH Bydgoszcz lesson observers, and I am sure that each school going through the same process would end up with a different list of its own.

Benefits: changes to induction and training sessions

When we got a positive response to the idea of being up front and quite focused about our initial observations concentrating on the 1st– and 2nd-year development record, we backed this up by running workshops in these areas, and in the following year’s induction week gave out the 1st– and 2nd-year development record and ran those sessions again.

And overall?

The result of this process is that this year, for the first time, within two months of the beginning of the academic year, every one of our new teachers was performing at least satisfactorily, but more often well or very well, in each of those key areas. It has also been an interesting process for us as the senior staff, as it has allowed us to see a crystallisation of our beliefs on what our teachers broadly need, and that has helped us to develop our teachers more effectiveley. The next step will be for us to look at what those beliefs say about us, and use that to develop ourselves. But that is for another day.

* Appendices are available in this Dropbox folder: http://bit.ly/IHJournal37appendices. Thank you to Tim for generously sharing these resources.

Author’s Bio: Tim is Director of Studies at IH Bydgoszcz in northern Poland, where he worked 15 years ago as Adults and Exams Coordinator, and has been a teacher and DoS for IH Toruń. He also worked for Qatar Petroleum for 8 years helping develop the English language competence framework for the energy and industry sector and print and multimedia materials to teach those competences.