Listening and self-access: a perfect partnership

by Arizio Sweeting

Have you ever asked yourself why your learners perform well in listening activities in the classroom, but do poorly in listening tests at the end of the course? Surely, if they are able to perform competently in listening practice in class, they should be able to do well in listening tests too. Ironically enough, this is not what normally happens. In fact, what normally happens is that while learners often handle listening lessons, they tend to struggle with listening tests.

Perhaps, on one hand, this is because in the second-language listening classroom, learners’ skills development is scaffolded by what Field (2009) calls ‘the comprehension approach’, a conventional approach in which the teacher leads learners through a sequence of focused practice stages such as context set, vocabulary clarification and different sub-skills practice. In listening tests, on the other hand, learners are left to their own devices and reliant on preparation for passing exams. In other words, learners’ performance in listening tests tends to be usually more dependent on exam preparation than the use of cognitive processes to negotiate listening information.

This may come to you as a blatant over-generalisation, but I’m also certain that there are many teachers out there who would agree with me. You’re now probably asking yourselves if I would have a solution for this issue and, to avoid the risk of sounding presumptuous, I would say I don’t. What I would like to say, however, is that in my search for ways to help my learners gain more out of listening, I have found a useful ally in learner training by encouraging my learners to use self-access for listening skills development and this is what I would like to share with you in this article.

The article is divided into two parts. The first part is entirely focused on describing a self-access listening project, which I shall refer to as SALP from now on and, the second part presents a few practical ideas for exploiting self-access listening to further promote skills and language development.

The Self-Access Listening Project (SALP)

SALP was an impromptu project which I conducted with a group of 15 pre-intermediate adult learners at the Institute of Continuing & TESOL Education on a five-week General English course in 2011. The main aim of SALP was to provide these learners with remedial practice in listening so that they could overcome lower scores achieved on previous listening tests. The participants came from a range of different parts of the world such as South East Asia, the Middle East, Africa and South America.

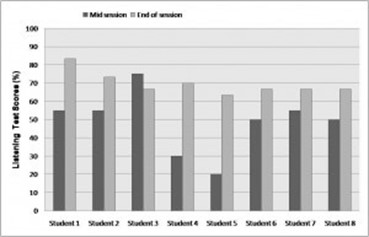

It is important to emphasise that these learners were also already receiving listening skills practice in their General English program. More specifically, they were receiving listening practice in both their Integrated Skills lessons, a component of their course which focused on skills and language development and in their Comm. Skills lessons, a component entirely dedicated to listening and speaking. Interestingly, these learners were dealing well with listening practice in these lessons, possibly because their skills development was being scaffolded by teacher-aided both top-down and bottom-up processes. Another important aspect about SALP is that it was a voluntary project i.e. the learners had the option of taking part in it or not. However, it is worth mentioning that the majority of the learners in the class chose to take part in the project and most of these learners were able to achieve the Pass grade of 63% on their end-of-the-session listening test, as illustrated in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1

The project was organised into a series of steps. The first step was the selection of thematic listening recording that would suitably supplement the kind of practice the learners were receiving on their General English course. Therefore, to avoid a clash with the themes in the coursebooks in the course program, I decided to use audio clips from reliable online sources which offered free, downloadable MP3 files. The listening files were then organised into thematic units such as animals, food, places and so on and stored on the learners’ USBs.

The second step was the design of listening booklets to accompany the audio clips and to include the type of test item which had been identified as problematic on the learners’ mid-session listening tests. Examples of these were multiple-choice questions, listing, gap-fills and true and false questions. Each booklet was designed to focus on one or two of these test items at a time to maximise learner exposure to them. For instance, the first booklet used in SALP included 10 listening practice exercises, each accompanied by 10 multiple-choice test items, which provided the learners with 100 items to use in self-access. In addition, the booklets contained a mix of different English accents, including recording by speakers from a non-English background, answer keys to the practice tasks and the transcripts for all the recordings.

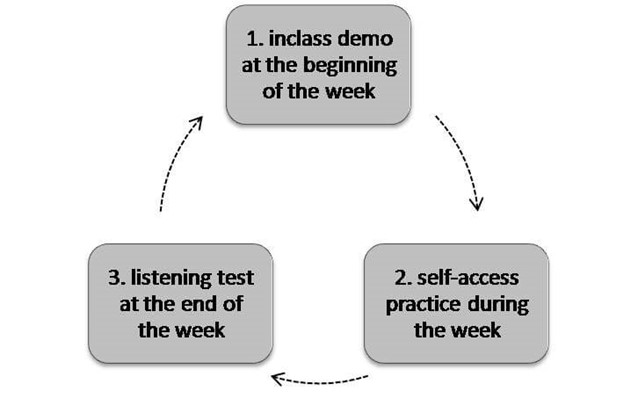

The third step was to establish the self-access practice with the learners and this was done in cyclical staging, as depicted in the diagram below:

As seen in the above diagram, the initial stage of the self-access practice took place in the classroom. During this stage, the learners worked on 10 listening test items with my support. For example, the learners were given time to read the test items on their listening practice sheet and then ask me questions about vocabulary, if necessary. The learners were also encouraged to use their learner’s dictionaries to check the meaning of unknown words. Then, the learners listened to the recording once to answer the questions. After that, they were given a minute to check with a peer to discuss their answers. They would then have another go at the tasks and peer check one more time. The learners would now receive an answer key and the transcript of the recording to check their answers. I would then replay the audio clip for them to listen to one more time while reading the transcript. Finally, I would get feedback from the group, playing the parts of the recording which learners had had difficulty with.

Once the classroom practice was finished, the learners received the instructions for the self-access practice outside the classroom. As an attempt to ensure they got the most out of the listening practice, I felt the need for standardising the self-access practice a bit. To do that, the learners received a separate answer sheet and the following instructions:

- Listen to each recording as many times as necessary.

- Enter the answers to the listening test items in your booklet.

- Try not to check your answers with the key or read the transcript before, during or immediately after you have had your first go at the recording.

- When you feel confident about your answers to each recording, enter them into your separate answer sheet.

- Check your answers against the key and highlight the answer you got wrong on the answer sheet.

- Listen to the recording again, and this time, read the transcript. Check if you are able to see why you got items X, Y or Z wrong. If not, make a note of these to discuss with the teacher.

- Repeat the same procedure for all the other recordings in the booklet.

The instructions above were an attempt to stop the learners from instantly checking their answers and wasting a valuable opportunity to maximise exposure to listening. For instance, by repeatedly listening to the recordings, the learners gain more familiarity with them and, consequently, increase their chances of unravelling features of connected speech, identifying potential distractors, perceive accented differences in the pronunciation of certain lexical items and more.

The second stage of the cycle i.e. the self-access practice took place outside the classroom. For this practice, the learners were given four and a half days in general. For example, both the material and the instructions for the practice would be given to the learners at the beginning of the week e.g. on Monday morning, and they would have until Friday morning to complete the whole listening practice.

The third and final stage of the self-access practice involved the learners gauging their progress with handling the test items by doing an innovatively-designed progress listening test. One innovation of this progress test was that it was managed entirely by the learners. That is, the learners were responsible for marking their own tests, and there was no expectation that they revealed their test scores. Another innovation of this test was that two recordings from the self-access booklet would be randomly selected each week and put into the test and novice test items were written to accompany them. One more innovative feature of this progress test was that it included a ‘surprise’ recording and questions to allow the learners the opportunity to measure if their listening skills and test techniques had developed with the extra practice outside the classroom.

SALP was run for a period of five consecutive weeks. After the initial cycle, once the learners became acquainted with the process, the self-access practice went into auto-pilot, and my role changed from teacher to facilitator.

Exploiting Self-Access Further: Practical Classroom Ideas

In this part of the article, I would like to share some practical ideas which could be used to exploit a self-access listening project like this for further skills and language practice.

Using Word Clouds: WORDLE

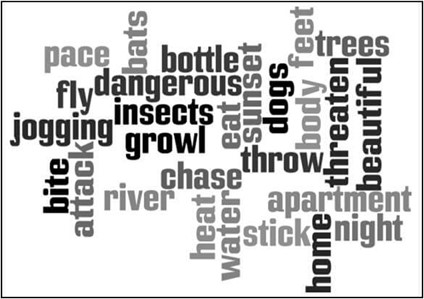

One of these websites, you could use to supplement your listening self-access project is [this link may no longer be valid www.wordle.net], a website which allows you to create word clouds by providing a text and then tweaking them with different fonts, layouts and colour combinations. Here are some ideas for using this web tool with your learners.

Use the transcript of the recording, select words to focus your learners on and paste them into the box on the website to create a word cloud, as in Figure 2. Once the cloud is created, format it to a desired appearance. After that, you will be given the option to save the word cloud onto the site and make it available to everyone else who uses it, or you can print it and photocopy the cloud for instant use. Another option is to use the Print Screen button on your computer and save it on Word to prepare a worksheet for your students. Once the word cloud is created, use it for grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation and speaking practice.

For grammar practice:

1. Get the students to categorise the words into countable and uncountable nouns.

2. Get students to separate the words into nouns, verbs and adjectives and then write grammatically correct sentences about the text.

For vocabulary practice:

1. Get the learners to form lexical chunks by matching verbs and nouns, adjectives and nouns etc. For example, to throw a bottle at someone.

2. Get the learners to individually categorise the words into groups and then test their partners if they can guess their categorisation criteria.

3. Get the learners to write odd-one-out exercises using synonyms and antonyms for the words on the clouds. E.g. growl, howl, bark, neigh

For pronunciation practice:

1. Get the learners to categorise the words according to stress.

2. Get the learners to find words with similar vowel sounds i.e. short and long sounds.

For speaking practice:

1. Get the learners to use the words to retell the listening passage to each other.

2. Get the learners to write a telephone conversation about the listening passage using the words on the cloud.

Taking the Recording for a Walk

One activity I find particularly useful, especially when setting up the self-access practice in class, is what JJ Wilson (2008: 138-9) calls ‘taking the recording for a walk’ in his book How to Teach Listening, (Pearson Education). Based on the thinking-aloud protocol method, a cognitive process in which the participants of an activity discuss ways to solve a task, you pause the recording at strategic points and ask learners questions to help them rationalise on the way they’re dealing with the test items. Another way of encouraging a more active and cognitive engagement with the test items is to get the learners to act out the items to generate language, increase the learners’ lexicon and better equip them for similar test items in the future. For example, imagine the following multiple-choice question:

What kind of animal are you afraid of?

a) Bats

b) Snakes

c) Dogs

Learners work together and act out a conversation for each of the answers above. By doing so, they’re activating enough schemata to allow the learners to focus more on cognition than recognition.

Building Crosswords Using Online Puzzle Makers

Another activity which can encourage the learners to use the transcript of the listening recordings for vocabulary practice is to crossword building. To create puzzles, the learners can use Web 2.0 tools such as http://en.puzzle-maker.com/crossword_Entry.cgi, which are available for free on the internet. Here’s a suggested procedure:

1. Get the learners to work in pairs and read the transcript of a listening recording and select 10 words to build a crossword puzzle.

2. Using a learner’s dictionary, get the learners to look up the meaning of the words they selected and write definition clues for them.

3. Take the learners to a computer lab and get them to work together and create a crossword puzzle for them using the website above.

4. Make sure you assist the learners with the instructions for using this website. For instance, make sure they separate each word and its clue with a slash "/" character and then press ‘Enter’ after each clue.

5. Emphasise to the learners that each clue can be as long as they like.

6. When the learners have finished creating their puzzles, get them to write down the answers to their puzzles.

7. Regroup the learners and get them to exchange puzzles with each other. After that, the learners help each other to check their answers.

Conclusion

As Scharle and Szabó (2000: 7) emphasise, ‘developing responsible attitudes in the learner entails some deviation from traditional teacher roles.’ This means that teachers need to re-evaluate their role in the learning process in order to start moving towards learner-centred attitudes by playing the role of facilitator and counsellor more often. It is advisable, however, that any change in roles should be gradual rather than abrupt or dramatic. Change requires patience and caution, especially as learners tend to be afraid of the uncertainties and risks involved in changes in general. Some learners also have negative opinions about alternative teaching methods and, therefore, respond suspiciously towards any autonomous initiative. For this reason, I believe that taking small steps in the classroom to long-lasting learning habits towards learner autonomy are very beneficial to reinforce motivation, self-confidence, learning strategies, cooperation and group cohesion.

References:

Scharle, Á. & Szabó, A. (2000) Learner Autonomy. A Guide to Developing Learner Responsibility. Cambridge University Press.

Wilson, J. J. (2008) How to Teach Listening. Pearson Longman.