by Tony Penston

Did you get the car repaired or did you have the car repaired? Many teachers would struggle to explain the difference between the two constructions - but the answer, it turns out, depends on the type of car you have.

The English language often offers a choice in lexis or grammatical pattern in order to convey a certain nuance. Sometimes the options can seem arbitrary, obliging the teacher to refer to their coursebook or other material to explain the difference. Sometimes the native speaker will go with what ‘feels’ right, but this can be dangerous, as we all know. But even then, is the coursebook correct? Coursebooks and grammar books often hide the full story in order to keep things simple, but in doing so they may actually be being a little unhelpful.

Besides differences within the one variety, globalization is causing the question to arise of whether the American English version of a language aspect is to be taught alongside the British English one – this happening especially in the case of business English.

While writing the second edition of A Concise Grammar for English Language Teachers, I availed of online corpora to find clarity for what some would call grey areas (and others gray areas!) of usage, and some of the results were quite interesting.

A brief note on my choice of corpus

Among the many online corpora available I found www.english-corpora.org ample and affordable for my needs. Its most relevant corpora for my work were the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA), containing over one billion words (1990-2019), and the British National Corpus (BNC), containing up to 100 million words (1980s-1993). There is also an up-to-date web-only corpus, but I rejected that in favour of the mixed media COCA and BNC. Here, I’m taking COCA as representing American English (AmE), and BNC as representing British English (BrE).

Another corpus for consideration was www.Sketchengine.eu This contains up to 70 billion words in each of several languages, and more functions than COCA, so it is an immensely powerful tool. However, it did not quite suit my needs as its data are web-only, and it takes a few clicks to ascertain data for BrE and AmE; but this is not to take away from its remarkable utilities, beyond my requirements. I tested correspondence between data in Sketchengine and Englishcorpora.org for many of my search items and none differed to any significant degree for my purposes, except with spoiled/spoilt, for which I have offered an explanation in the quiz answers at the end of this article.

Six areas of curiosity

In this article I have addressed six areas of curiosity, even consternation, concerning choice of lexis and/or grammatical form, even spelling. Each section is accompanied by a quiz, for which the key is at the end of this article. Have fun!

- Causative (passive) with have or get

- should and ought to

- -ed or -t past endings

- Modal perfect for negative deduction – American English

- Different from/to/than

- The spelling of used to in negative and question forms

1. Causative with have/get

By using have or get + object + past participle we say how we cause something to be done, or experience something. On first meeting, learners will be happy to be told there’s little difference between have and get in this construction, but in fact there are some clear preferences. Test your thoughts in the quiz below.

Quiz 1

In each sentence below, mark the form, had or got, according to which you think has the higher frequency of use (the asterisk represents any word). And if this is too easy for you, under ‘COCA frequency’ also tick ✓ which item has a greater than 10:1 ratio of use.

2. Should and ought to

You may tell your Ss that should and ought to have the same meaning, but be ready for the response, “Then why are there two different words for the same thing?” It’s a good question, yet surprisingly, many grammar books abstain from answering it, apart from some stating that should is used more often than ought to.

Claims of differences in formality may be hard to prove, whereas written/spoken can be a more agreed divide. For example, the phrase it should come as no surprise… is almost exclusively found in writing. Conversely, there doesn’t seem to be any exclusively spoken instances of ought to, although oughtta/oughta, being colloquial in itself, would have some preferences, e.g. You oughtta treat me with more respect, pal.

Reasons for choice might include the fact that ought to can better carry an ‘admonishment’ nuance, as in You nearly killed that guy, you ought to be more careful, and this may explain the posit of ‘strength’ difference (found online); i.e. ought to, in such contexts, may likely be used in addressing someone of lesser authority/power. Relatedly, ought to may be seen to be used for stating what’s morally or justly right, and should for general advice, e.g. You should always finish a course of antibiotics.

Quiz 2

Answer the following questions according to their form.

1. I should have VERB and I ought to have VERB are used with almost equal frequency in BrE. True/False

2. Should be a law against is used more frequently than ought to be a law against in both BrE and AmE. True/False

3. The frequency ratio of I shouldn’t to I oughtn’t in AmE is

A. 5 to 1 B. 50 to 1 C. 500 to 1 D. 5,000 to 1

4 The frequency ratio of should I to ought I (to) in AmE is

A. 6 to 1 B. 60 to 1 C. 600 to 1 D. 6,000 to 1

Note: the phrase you should have VERB is by way of a shortcut to avoid conditionals like If you should see John…

3. -ed or -t past tense endings

Verbs like burn, dream, smell, have either –ed or –t past endings. Brief explanations on the web often simply state that the -ed ending is used in American English (AmE) and the -t in British English (BrE). But is that the whole story? Try our next quiz.

Quiz 3

Use a tick ✓ to mark which past tense verb form is preferred in each of the AmE and BrE varieties (represented by the frequencies in COCA and BNC respectively).

4. Modal perfect for negative deduction – American English

5. Different from/to/than; what’s the difference?

6. The spelling of used to in negative and question forms

Which is correct: She didn’t used to or She didn’t use to? And Did she used to or Did she use to?

Most teaching/learning materials adhere to the rule whereby the auxiliary verb (do-did) carries the tense and therefore the main verb (use) must be in the bare infinitive, e.g. we don’t say She didn’t wanted to. But how many users respect that rule? We know that English grammar rules are as people make them; what about the spelling?

Quiz 6

(PRON = pronoun)

- Which spelling is preferred, PRON didn’t used to or PRON didn’t use to?

- Which spelling is preferred, Did PRON used to or Did PRON use to?

- Is the preference more pronounced in the negative (question 1 above) or the question forms (question 2 above)? Note, there may be a difference between AmE and BrE here.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Now, take a moment to make sure you’ve answered all of the questions above - as we’ll now be looking at the answers, before moving onto a brief conclusion about what this all means.

Answers

1. Causative with have/get

The highlighted ratios are greater than 10:1

*The data numbers are actually 11 and 0. I’ve changed them to 12 and 1. There’s a similar adjustment in Quiz 2.

Conclusions to be drawn:

1 and 2: The formality of have over get is apparently revealed here by the fact that one has one’s higher quality items repaired but gets one’s lower quality ones fixed.

3, 4 and 5: Only a misfortune that is apparently well deserved merits the choice of get.

Coursebooks and other materials should take these findings into account.

2. Should and ought to

Conclusions to be drawn:

That ought to is often used to state what’s ‘right’ is apparently borne out by the fact that the frequency difference between there should be a law against it and there ought to be a law against it is relatively small in AmE (27:17). Syllabuses ought to include ought to in this and similar contexts early on in their treatment of the grammar. Regarding negatives and questions (rows 3 and 4) there is ample evidence to suggest that not until a more advanced level (around C1 or even C2) should I oughtn’t and ought I (+ with other subjects) enter the syllabus. The negative oughtn’t (row 3) might also merit being held back until advanced level.

3. -ed or -t past endings

A tick ✓ marks the verb which has the higher frequency of use in each variety (in the context PRON/NOUN ‘verb’ *).

* The frequency ratio of burned to burnt in BrE, 297:194, is not greatly significant. However, similar or more significant results were provided by phrases such as were burned and were burnt (50:33) – apologies for including past participles for that.

† With spoiled/spoilt in BrE the difference is tenuous. I discounted adjectives, e.g. one spoilt brat, but in sentence-final position the word could occasionally be interpreted as a participle or an adjective. I counted participles, e.g. in the fruit was spoiled/spoilt [by the sunlight], but eliminated complements, e.g. she seemed spoiled/spoilt.

For those who are interested, Sketchengine.eu disagreed with Englishcorpora.org, with BrE (.UK sites) preferring spoiled with reasonable significance. By way of explanation I would guess that UK web-only (up-to-date) data are showing a modern preference for spoiled.

Conclusion to be drawn:

The facile statement, ‘-ed for American English and -t for British English’ is easily disproved with corpora findings.

4. Modal perfect for negative deduction

The answer is: B 12 to 1

Conclusion to be drawn:

Especially in an international teaching context, the strong AmE preference for must not have makes it requisite when teaching the modal perfect.

5. Different from/to/than; what’s the difference?

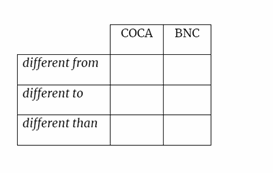

The table below shows the ranking and frequency for each phrase.

Conclusion to be drawn:

Different than should not be regarded as an ‘also ran’ in American English. The frequency ratio of different from to different than is about 2½ to 1 (26,747 to 11,158). This contrasts greatly with British English, where the frequency ratio of the same phrases is more than 60 to 1 (3,246 to 50). British English speaking teachers, and authors, should not allow this 60:1 preference to cause them to neglect the creditable American English alternative.

6. The spelling of used to in negative and question forms

For questions 1 and 2 the answers can be seen in the table below, i.e. the spelling of used to is preferred over use to in negatives and questions (in both AmE (COCA) and BrE (BNC)).

For question 3, we can see that the preference for used to is more pronounced in the negative context for AmE (COCA), but interestingly, in the question form for BrE (BNC).

Only pronouns (PRON) have been used as the subject, for ease of operation. On the subject of media, admittedly some of the data are extracted from movie and TV audios; however, the choice of spelling still has to be made by the software engineers, so I would assert that the data are still valid.

*The capital D has been maintained to make the interrogative force instantly clear – other environments besides initial position have been counted.

Conclusion to be drawn:

If a clear majority of users prefer the spelling used to in negative and question forms, it may be time for teaching materials to acknowledge this and treat the alternative spelling as fully acceptable.

General conclusions

Teaching and learning materials may withhold or minimize information that the teacher would be better off knowing. If English usage forms are decided by its users, then corpora must serve as the essential source for the identification of those forms, and the findings should be presented to the teacher for use as they see fit. Teaching materials could also include some corpora frequency figures as a matter of interest for learner and teacher alike.

References

Penston, T. (2024) A Concise Grammar for English Language Teachers, second edition. Greystones: TP Publications

www.english-corpora.org (data as at time of publication)

www.Sketchengine.eu (data as at time of publication)

Author Biography

Tony Penston is a semi-retired EL teacher, holding a TCL Dip TESOL and an M. Phil in Applied Linguistics. His interests are split between teacher training, phonetics, and teaching according to immersion learning principles. Under the business name of TP Publications he has self-published A Concise Grammar for English Language Teachers, Essential Phonetics for English Language Teachers, Using Drills in English Language Teaching, and A History of Ireland for Learners of English.

Tony Penston is a semi-retired EL teacher, holding a TCL Dip TESOL and an M. Phil in Applied Linguistics. His interests are split between teacher training, phonetics, and teaching according to immersion learning principles. Under the business name of TP Publications he has self-published A Concise Grammar for English Language Teachers, Essential Phonetics for English Language Teachers, Using Drills in English Language Teaching, and A History of Ireland for Learners of English.