Using electronic concordancers in the language classroom

By Dana Taylor

In this article, I will identify uses for corpus tools in the language classroom and critically reflect on the advantages and disadvantages of concordancing as a teaching strategy. I will also offer recommendations for English language teachers to use concordancing in their own classrooms.

In recent decades, researchers (e.g. Kheirzadeh & Marandi, 2014) have investigated ways in which language corpora and concordancers help English language learners (ELLs) develop sociolinguistic and sociopragmatic knowledge for success in academic and professional contexts.

According to Anwardeen, Luyee, Gabriel, and Kalajahi (2013), concordancing tools are “computer programmes that search collections of (usually) authentic spoken and written texts, known as language corpora, for lexico-grammatical patterns and norms of the discourse community presented in concordance lines” (p. 84). ELLs can employ a concordancer to check, learn, and share vocabulary. They do this through comparing their understanding of lexis and grammar with real-world sources from general or specialised corpora.

My teaching and learning context

I teach an internship course for post-secondary ELLs offered by the International Academy of Business Studies (IABS) in New Zealand. (Identifying details have been changed, and pseudonyms are used for the organisation and its courses.) My Work Placement (WP) course supports students in developing applied language and job skills. WP students need to identify and analyse genre-specific target language features, owing to the challenges they face decoding and producing authentic professional communications. For example, my students need to use contextual lexico-grammar and sociopragmatic structures when writing business letters and reports. They are also under pressure from family members to obtain a job after graduation, leading to a strong focus on self-directed learning and employability skills in IABS courses (senior manager, personal communication, September 12, 2018).

Corpus tools for English language learners

Utilising corpus tools for vocabulary development and communicative competence would be a new strategy for my WP students. In the past, ELLs have identified the rhetorical and lexico-grammatical devices of model job application letters in order to replicate these—along with statements of their attributes and achievements—in their own cover letters. Thus, concordancers should provide WP students with meaningful examples of functional words and phrases in correct context and appropriate sociopragmatic register to serve the rhetorical purpose of—in the case of writing a cover letter—being offered an interview (Chen, 2004).

Needs-based teaching resources

Chen (2004) found that free online concordancers, such as WordSmith Tools (Scott, 1996) and Lextutor (Cobb, 2004), supported teachers’ design of instructional resources from authentic texts. ELLs used keywords to locate example concordance lines from a corpus, notice target language patterns, and guess and check grammatical rules in correct context. WP students would probably benefit from using a general corpus in conjunction with a small, teacher-compiled corpus of business letters.

Data-driven learning

The data-driven learning afforded by concordancing encourages ELLs to identify language patterns. According to Yoon (2008), students take ownership of language learning by noticing common formulaic expressions (e.g. I look forward to speaking with you) and collocations (e.g. speak + with [+ someone]). Hafner and Candlin’s (2007) study of students using a concordancer to write legal papers provided pedagogical implications and instructions for concordancing, which would

help me design concordancing activities.

Concordancing presents the following advantages and disadvantages to teachers and ELLs in tertiary contexts:

Advantages of concordancing

Autonomous learning. ELLs’ autonomous use of concordancers helps develop vocabulary, grammar, and genre knowledge in authentic, meaningful contexts. Yoon (2008) reported that, by using corpus technology, students became aware of their difficulties writing genre-specific texts in English. WP students would indeed benefit from a concordancer if it became a language-checking tool for autonomous self-monitoring per Gavioli and Aston’s (2001) recommendation.

Exploratory learning. Hafner and Candlin (2007) found that concordancing gave ELLs motivation for lifelong exploratory learning because it satisfied their personal and professional curiosity about new words. WP students could use the concordancer as a problem-solving device to notice collocations, conventions, and connections between grammar and vocabulary in professional texts. This may also allow them to transfer word knowledge and usage patterns to their pleasure reading and academic writing.

Disadvantages of concordancing

Need for learner training. Chen (2004) warned that the immense data accessed by corpus technology might overwhelm ELLs. Therefore, learners need to receive concordance training to become critical participant-observers: engaging with the text, inferring patterns, and reacting pragmatically (Gavioli & Aston, 2001). Learner training will be important for my WP students, as it will help them focus on noticing language patterns instead of just obtaining models of professional texts (Hafner & Candlin, 2007).

Barriers to students’ use. Yoon (2008) observed that barriers to students’ use of concordancing were their English proficiency and/or lack of access to corpus technology. This could result in students being put off by the effort required to read and decode concordance lines. Nevertheless, Hadley (2001) recommended that ELLs access concordancers independently to gain adequate exposure to target language found in authentic texts.

Conclusion and recommendations

In summary, specialised and general corpora give ELLs access to high frequency, contextual vocabulary from relevant general, academic, and professional sources. WP students are exposed to culturally-bound formulaic expressions in the workplace, so form-focused instruction should help them notice collocations and word meanings, thus building their language awareness and sociocultural understanding (Yoon, 2008). Although corpus tools are freely available to my students, I will need to spend time creating classroom materials to integrate concordancing into the WP course. Concordancing will require effort on my students’ part, too, since corpora-based language learning will be unfamiliar to them. However, as Hadley (2001) observed, data-driven concordancing could prove a useful and relevant teaching strategy for WP students to improve their vocabulary knowledge and writing skills for academic and professional success.

Following are my recommendations for using concordancers in your ESOL classroom:

- Access a concordancer and practise with a sample text before trying it with your students. Here are the steps for one concordancer, Cobb’s (2004) Lextutor:

– Go to the Lextutor website, https://lextutor.ca/

– Click on ‘Concordance’.

– Click on ‘Text-based Concordances’.

– Enter the title of your text in the small box.

– Paste your text (e.g., from a textbook, document, or website) into the large box.

– Click ‘Submit’. - Use the concordance to help students identify collocations, idioms, subject-verb agreement, tenses, conjunctions and other language patterns. Here are two sentences that emerged from the concordance of a job application cover letter:

– I have BEEN a customer of ABC Sales for

several years.

– I have always BEEN impressed by the

quality of service.

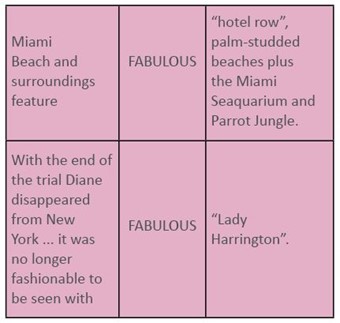

There are opportunities here for ELLs to guess and check rules for the present perfect simple tense. They could then create their own example sentences. - To help ELLs become language researchers, ask them to go to lextutor.ca, click on Concordancer > Clean Sentence Concs, and then enter a word of your choice, or theirs, into the box. For example, for the word ‘fabulous’, the following two sentences emerge:

Author's Bio: I’ve taught ESOL in New Zealand since 2003. I hold an LTCL Diploma (TESOL) with Distinction and a Master of TESOL Leadership with Distinction. I’m currently working towards a PhD in Applied Linguistics. As Assistant Dean, I manage business and tourism programmes, teach vocational English, and train teachers.

|

References: Anwardeen, N. H., Luyee, E. O., Gabriel, J. I., & Kalajahi, S. A. (2013). An analysis: The usage of metadiscourse in argumentative writing by Malaysian tertiary level of students. English Language Teaching, 6(9), 83-96. Chen, Y. H. (2004). The use of corpora in the vocabulary classroom. Internet TESL Journal, 10(9). Retrieved September 4, 2018, from http://iteslj.org/Techniques/Chen-Corpora.html Cobb, T. (2004). Range for texts v.4 [computer program]. Accessed September 15, 2015 at http://www.lextutor.ca/cgi-bin/range/texts/index.pl Gavioli, L. & Aston, G. (2001). Enriching reality: Language corpora in language pedagogy. ELT Journal 55(3), 238-246. Hadley, G. (2001). Concordancing in Japanese TEFL: Unlocking the power of data-driven learning. Retrieved September 25, 2018, from http://www.nuis.ac.jp/~hadley/publication/jlearner/jlearner.htm Hafner, C. A. & Candlin, C. N. (2007). Corpus tools as an affordance to learning in professional legal education. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 6, 303-318. Kheirzadeh, S., & Marandi, S. S. (2014). Concordancing as a tool in learning collocations: The case of Iranian EFL learners. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 98, 940-949. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.503 Scott, M. (1996). WordSmith Tools v.1 [computer program]. Accessed September 15, 2018 at http://lexically.net/wordsmith Yoon, H. (2008, June). More than a linguistic reference: The influence of corpus technology on L2 academic writing. Language Learning & Technology, 12(2), 31-48. |