Kissing a stranger: Cultural competence

By James Egerton

Why work for International House? Among a plethora of reasons is the great opportunity to move from one affiliate to another around the world; barring disgrace at one IH post of course, in which case said individual will be tarred and feathered, and mentioned only in hushed whispers like Voldemort’s in staff rooms across the IH network.

For the vast majority of IH colleagues though, this opportunity remains open, and while pedagogical proficiency must be proven through qualifications, what about cultural competence in understanding what students might respond best to? After all, being linguistically competent but culturally oblivious can cause a range of problems for both learner and teacher, and as I’ll discuss further on, there are more proactive ways to prepare for new cultures than through trial and error.

Have you ever kissed a stranger?

My inspiration for this article came at the beginning of a CELTA course I was observing here at my new home at IH Rome in September. With the noble aim of encouraging students to mingle with the present perfect, a trainee showed me her plan to include ‘Have you ever kissed a stranger?’ in the question list - on Day 3 of their acquaintance! Cold, cautious and prudish after two years in Latvia had re-exposed my Britishness, I balked and blushed (did I gasp a couple of times?) and asked said trainee if this was overstepping personal boundaries.

My concern was met with confusion - “Who is this new guy? Has he just escaped from the Vatican down the road?” - and was shown to be groundless, as the students didn’t bat an eyelid at the question and happily shared their personal stories. This left me to reflect on my current cultural incompetence, and wonder what else might fly while teaching in Italy. Indeed, less concern about encroaching on personal boundaries allows for a much greater range of topics, and leaves more of students’ mental capital to invest in communication and language focus rather than stepping on egg shells.

“Your experience is limited, young grasshopper! It proves nothing!”

Guilty, your Honour! I’m a relative novice, having only been teaching in Spain at a private academy (2012-2016), IH Riga in Latvia (2016-2018) and now at IH Rome. This is why I asked several IH colleagues past and present about their experiences of TEFL-ing within a variety of cultures, to add some more perspectives to my own.

I’m aware of the fallacy of solely relying on anecdotal evidence, but here are several other viewpoints to sit alongside my own before we consult academia...

Kelly Brennan, IH Palermo (London School) to IH Riga: ‘My first comment after teaching a class in Latvia was ‘wow they’re quite serious’. Sicilians, on the other hand, were very keen to showcase their talents from the word “go”... Some of my tried and tested hilarious anecdotes were met with a blank stare or a raised eyebrow in Riga.’

Sam Goldie, IH Bydgoszcz to IH Sevilla: ‘In general terms, Polish students are certainly more intolerant of ambiguity and you get a lot of classes that need warming up before they’re welcome to share. In a nutshell, Spanish students are hard to shut up and Polish students are hard to get talking.’

Robbie Hancock, IH Santiago de Compostela to IH Riga: ‘I think some of the “lighter” activities didn’t work as well in Latvia as the Spanish are a lot more “light-hearted” on the whole. I also found that some of the Latvian/Russian students’ desperation for constant correction could get in the way of an activity.’

Lisa Wilson, IH Toruń to IH Palermo: ‘Polish teenagers on the whole tended to be more informed about global, political and social issues than here in Sicily.’

Chris Jones, IH Apollo Hanoi to IH Rome: ‘I’d been led to believe Vietnamese students would be near-silent in class, lest they make a mistake. On the contrary, as long as the topic was well chosen (definitely not politics or celebrities who aren’t Taylor Swift), the students were keen to communicate, and not overly concerned with being accurate.’

“All anecdotal! Where’s the academic research?”

A caveat to start: national stereotypes are as lazy as they are silly: the majority of Brits don’t sit down for 5 o’clock tea, not every American is a gun-slinging redneck (etc.). In the worst cases, stereotypes are weapons for racial discrimination. Every person is an individual, with their own motivations, expectations and baggage, and the colour of someone’s passport (or anything else for that matter) is no precise indicator to their behaviour.

That said, several large-scale studies have consistently uncovered variation in average personality around the world due to genetic, environmental and political-historical factors (Jarrett, 2017); knowledge of which can facilitate the key TEFL business of cross-cultural interaction (Allik and McCrae, 2004). This is why, while never taking our eyes off the individuals in front of us, I think that more attention should be paid to cross-cultural personality research to inform our choices as educators, especially when getting used to a new culture in the first months.

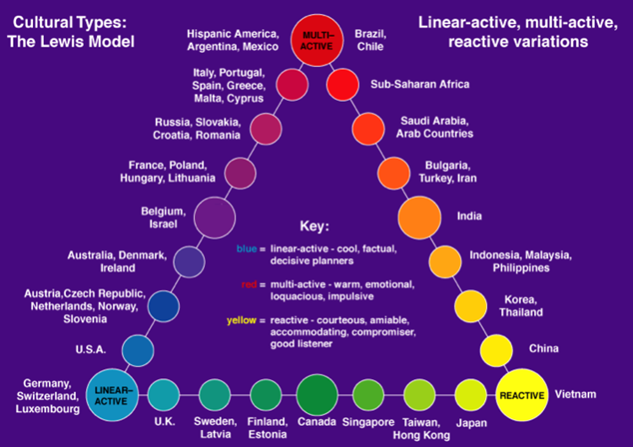

So where to look? There are several models and studies available, but one which I particularly like is the Lewis Model of Culture (Richard, not Michael!). This was introduced to me by the brilliant ILC IH Brno DoS Dave Cleary at the Trainer’s Weekend earlier this year (next Trainer’s Weekend in February 2019!).

The Lewis Model is based on data drawn from 50,000 executives at residential courses and more than 150,000 online questionnaires to 68 different nationalities, so although it’s an extensive numerical pool, it could be considered socio-culturally skewed and, like any study, it’s incomplete (“I was never asked!”).

But despite its imperfections, the Lewis Model remains a handy reference trusted worldwide in a range of industries, for example in the financial sector as ‘the authoritative roadmap to navigating the world’s economies’ (Wall Street Journal cit. CultureCatch, 2009).

Of course, many individuals deviate from the national average (note Chris’ testimony of his Vietnamese learners differing from the Lewis Model characteristics), particularly considering employment. But what are the implications for teaching English? Well, for starters: consider the difference between the typical classroom of Chinese and Portuguese students; or the ramifications for one person from each culture doing pair work in a multi-cultural group.

So what you’re saying is...?

Language translates but content doesn’t. At IH, we expect trained, professional teachers with excellent knowledge of language and pedagogy, but cultural awareness of the teaching context is usually learned on the job (often through a drawn-out cycle of trial and error). Of course, as was the case with the CELTA trainee, cultural awareness is second nature to teachers who share a culture with their students, but is worth serious investigation if not. How open is the average student in this culture, and how might this affect your teaching techniques? How might they process language – logically or emotionally? What might your students be comfortable discussing?

As Tomalin and Stempleski argue (cit. Sadtono, 2009), ‘communication, language, and culture cannot be separated’. So if real communication is to take precedence over teacher ‘delivery’, we should focus on who, not just what we teach: understanding a person’s culture and identity is paramount in creating an optimal learning atmosphere and choosing relevant and engaging topics. Indeed, when kissing a stranger sounds standard in one place and saucy in another, it’s more than the English language that we need to take into account in the classroom. Consulting the Lewis Model of Culture can really help with this.

Many thanks to the following IH colleagues past and present who helped me by sharing their experiences (in alphabetical order, not favouritism): Alycia Messing; Chris Jones; Flo Feast-Jones; Kelly Brennan; Lisa Wilson; Robbie Hancock; Sally MacAndrew; Sam Goldie.

Author's Bio: James is a Delta-qualified teacher and teacher trainer currently working at International House Rome Accademia Britannica. He studied French and Spanish at university before teaching in Spain for four years and Latvia for two, before arriving in Rome a few months ago. He has taken regular in-house teacher training sessions, is an IHCYLT course tutor, a CELTA TinT until Christmas, and has presented several webinars and IH conference talks. He blogs on ELT at www.jamesegerton.wordpress.com.

|

References: Allik, J. and McCrae, R.R., 2004. Towards a Geography of Personality Traits: Patterns of Profiles Across 36 Countries in Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology 35 (4), January 2004, pp.13-28. Available at: http://bit.ly/2zuS95p (Accessed 15/9/2018) Cross Culture, 2015. The Lewis Model – Dimensions of Behaviour. Available at: http://bit.ly/2PCe1WF (Accessed 13/9/2018) CultureCatch, 2016. A Global model of Cultures – A Trusted Approach. Available at: http://bit.ly/2SS1xJg (Accessed 25/9/2018) Jarrett, C., 2017. Different Nationalities Really Have Different Personalities, BBC Future. Available at: https://bbc.in/2RAAf8y (Accessed 15/9/2018) Mendoza-Denton, R., 2012. Cultural Stereotypes, or National Character? Available at: http://bit.ly/2JDeiTA (Accessed 15/9/2018) Sadtono, E., 2009. Cross-cultural Understanding: A Dilemma for TEFL. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46141814/download (Accessed 19/9/2018) Wurgaft, L.D., 1995. Identity in World History: A Postmodern Perspective in History and Theory, Vol.34 No.2, Theme Issue 34: World Historians and Their Critics (May 1995), pp.67-85. Available at: http://bit.ly/2yQcJNR (Accessed 15/9/2018) |