Delegation – letting go or losing control? by Maureen McGarvey

Delegation is something which many managers feel they do, and think they are good at doing. Ask their staff though, (especially those to whom they delegate) and you may get a very different answer. Delegating effectively brings with it obvious benefits for the manager, the delegate and the organisation. Yet too often, delegation deteriorates into a clumsy and botched process which takes a great deal of time and effort to rectify – and which certainly puts many people off delegating more in the future!

What exactly is delegation? Here’s a definition:

[Delegation is] …the process of entrusting authority and responsibility to others so that work can be carried out.

However, delegation is not about giving up ultimate authority and responsibility for the work. Delegation is not abdication! It is a shift of decision-making authority from one level in the organisation to another, but the person who delegated the work remains accountable for the outcome of the delegated task.

Reasons for delegation

1. To free the delegator’s time for other work

This is the most common reason for delegation, and, I think, one of the most problematic. Many managers delegate because they feel overloaded, which is understandable; but repeated need to delegate may mean that managers need to analyse their own workload and the scope of their own job description in more detail. If you repeatedly have to delegate a particular task, for example, then that task needs to become part of someone else’s job, as it clearly can’t remain part of yours! In addition, effective delegation takes time; time to explain the parameters of the task, time to train, time to support, time to ‘keep tabs’. A manager who delegates and expects to have more time as a result is, in the beginning at least, in for a bit of a shock. However, delegating routine tasks (for you) to someone else (for whom they are not routine, but something new) can free up the manager’s time for thinking/planning/reading – activities which are often put on the back burner because we are ‘too busy’.

2. To develop staff

This reason for delegation has a lot to recommend it. Delegation with this intention can increase experience and skills, involve staff more in the life of the school and raise awareness of different aspects of school life. Language Teaching Organisations [LTOs] are complex entities, and delegating a task to a teacher, which means they need to work closely with an administrative staff member, can help to make that teacher aware of the demands and pressures on the admin staff member. However, all too often, decisions are made about delegating tasks for a whole range of reasons, with ‘and of course, it’s developmental’ being tagged on at the end as the ‘moral reason’. If it’s being tagged on in this way, it probably isn’t developmental at all. You know it – and, rest assured, so does the person you are delegating to! As in so many things, it’s best to be upfront from the outset. If a delegate expects a task to be developmental and finds it’s a mundane task they are hardly likely to be motivated.

3. To cover for a manager’s absence

If you think you are indispensable, you are doing yourself, your colleagues and your LTO few favours. It’s part of your responsibility as a manager to ensure that work doesn’t ‘freeze’ when you are away. Some managers fear delegating for this reason, as they worry that the delegate will be better than they are. If the delegate is good at the job – you’re lucky! You have discovered a staff member with real potential, and can develop them accordingly. You don’t have to feel they are after your job; they want their own job! Delegating to cover for your absence can allow them to raise their game in a way you [and they] might not have anticipated.

4. To cover for gaps in the manager’s own abilities

This is a commonly under-used reason for delegation, probably relating to managers’ fears of being seen as ineffective or weak. But it is obvious that one person cannot possess all the knowledge and experience necessary to fulfil all tasks and the recognition of this is an important part of a manager’s self-awareness. Using the superior ability of the delegate as a learning opportunity thus makes sense for the manager. This is especially true where managers work as part of a team and where they use delegates’ skills to complement their own. As many LTOs move towards more of a matrix structure, with project teams shifting and being reformed frequently, we could, perhaps, view this less as delegation and more as skills exchange or transfer.

Points to Consider

If the work is boring or menial, think twice before you delegate it. I know that we said earlier that freeing up the manager’s time is a key reason to delegate, but staff will quickly realise if you delegate all the ‘dull’ stuff and keep all the nice bits for yourself. Think of regular tasks which you might be tempted to delegate for this reason; rather than delegating them, can you build them into someone’s job description so they can take responsibility from the outset?

It’s worth pointing out that managers who are promoted from the teaching staff [which we all are] can have a tendency to stick very close to what they know as teachers, and not develop the skills they need to lead and manage. This can be disguised as ‘staying in touch with the staff’ or ‘keeping my hand in’ – both important things to do, and both things which allow you to feel you are being a hands-on manager. However, you’ve been given a management role and that means you, as a manager, have to learn and develop new skills. So, while discussing and deciding on the best way to organise resource books may be something you feel comfortable with, it might be better to delegate that task to a teacher [who actually uses the books] and tackle the financial report, or sales projections, or off-site class timetable, which you have been avoiding. Oates [1993] calls this ‘avoiding the funnel of specialisation’. This type of delegation can also encourage and develop a team approach.

The next point is my Golden Rule for delegation. Delegate results, not tasks. In other words the manager tells the delegate what needs to be achieved, rather than specifying the procedure to be followed. Obviously, this will depend on the nature of the work to be delegated and on the experience of the delegate but, used appropriately, delegation enables staff to show personal initiative “beyond the scope of their normal work but within a set of company values” (Oates, ibid). Delegating results indicates very clearly that you trust the delegate to find their way, rather than following your prescribed set of steps. The earlier claim of ‘delegation is developmental/motivating’ is less likely to be true if the delegate has absolutely no say in how they arrive at the outcome. It also helps the delegate to see the inter-connectedness of systems and processes and make their own creative leaps in solving problems. If you identify the problem you wish to tackle, and let the delegate know what the problem is and what outcome you want, you are likely to have a more involved and committed staff member as a result. And you may gain some unexpected insights as a bonus.

Choosing the right person to delegate to can be quite difficult, particularly if you have a limited number on which to draw. We all have staff members who are keen, eager and enthusiastic, and our thoughts often turn to them first. However, I would suggest that we also need to consider those ‘more difficult’ staff members. Staff notice if the same people are asked to undertake projects, and this can cause resentment.

Sometimes, involving a more difficult staff member can lead them to realise aspects of the LTO which they were unaware of, making them less judgemental as a result. Of course, it’s not as pleasant for the manager! But if we truly want to develop all staff, we have to be even-handed with the opportunities we offer, and this includes delegation. The delegate also needs to understand why the work has been given and its importance. It may be perfectly obvious to the manager why this is the case, but the delegate may simply feel that s/he is being imposed on if the reasons are not made explicit. A great deal of goodwill can be lost by mangers simply neglecting to explain their rationale properly.

Success in delegation depends heavily on the manager’s own attitude. Being afraid that work will not be so well done by the delegate as by the manager can be partly countered by managers reminding themselves that the reason they have their jobs is because they are expected to be able to do the work involved. If their expectations of the delegator are not unreasonably high, then there is less likelihood of disappointment. This is a case for completed work being “good enough” rather than perfect.

A different fear may be that the manager is worried that, as Impey and Underhill [1994] put it, s/he will “relinquish the glory of success while retaining ultimate responsibility for failure.” Delegation is often resisted by managers who fear they are undervalued or who need to take the credit for work completed. Reminding themselves of their role as leaders may partly help to overcome this, but it is a very real issue in many organisations.

Another problem may be the manager’s inability to let go of the work. This might result in over-supervision (see below) or in the manager expecting the delegate to carry out the work in exactly the way that s/he would do it. Having delegated, managers need to be able to detach themselves sufficiently to let the delegate do the work. Micro-managing (sometimes called ‘parrot delegation’, like the parrot on the shoulder of a pirate) can stifle any enthusiasm very quickly.

Support and Feedback.

Some support features to consider are:

- Providing a clear summary of the result you want to achieve

- Setting the time parameters (when this needs to be completed by)

- Setting regular meetings /update sessions

- Helping the delegate to manage their own workload to allow for the delegation project

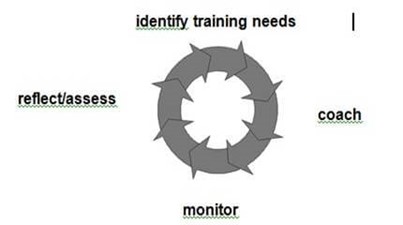

- Providing training and support for the delegate, perhaps in the form of coaching. A Coaching Circle [see below] is a helpful one to consider.

With this model, the reflection/assessment stages are built in, and this allows for feedback on the delegation process, which needs to be two-way for it to be truly effective. This feedback should, ideally, be two-way. Just as the delegate needs to know how s/he worked with the project, so too does the manager need to know how well the process was handled from the delegate’s perspective, and what the LTO could do better next time.

Delegation offers individuals and teams a powerful way to develop, to raise awareness, to work in cross-functional teams and to achieve remarkable (and sometimes unexpected!) results.